I equipped this test Royal Enfield with a combination of AndyStrapz canvas panniers, a Wolfman duffel, and a Pelican case rack trunk for a traverse of the Grand Canyon's North Rim

I equipped this test Royal Enfield with a combination of AndyStrapz canvas panniers, a Wolfman duffel, and a Pelican case rack trunk for a traverse of the Grand Canyon's North Rim

Just as our instinctive mental image of an expedition vehicle is more than likely a Land Rover 110 or Land Cruiser Troopie equipped with a roof rack loaded down with jerry cans and sand mats, so our image of an adventure motorcycle is likely to involve a giant BMW GS bulging with several square meters of aluminum sheet artfully folded and welded into rugged panniers and trunks covered with flag stickers from far-off places.

Thousands of the owners of these bikes have actually been to those far-off places. But how many riders chose those aluminum cases based solely on Long Way Round videos and magazine articles? How many remained satisfied with the approach after several thousand miles of travel? How many riders switch to soft luggage later on—and by the same token, how many riders start out with soft luggage and later switch to hard cases? Is there an overwhelming argument in favor of either, or is the choice simply a matter of trade-offs and priorities?

The debate has been the subject of endless forum threads begun by curious and innocent new riders. Replies generally fall into one of two categories: 1) “USE THE SEARCH FUNCTION!” or 2) Fifteen pages of opinions backed by rock-solid logic (and sometimes rock-solid experience) but little nuance. It’s either hard-luggage-is-the-only-way-to-go or soft-luggage-is-the-only-way-to-go.

The basic arguments for each are easily summarized. Soft luggage is less expensive, significantly lighter (with the equally important resultant benefit of a lower center of gravity), and not as likely to injure a foot or leg caught between luggage and ground during a spill or when working though rock gardens or sand. Soft luggage rarely requires special brackets to mount, generally results in a narrower bike profile, and can be compressed even further for shorter trips. If a soft pannier clips a rock or other obstacle during slow-speed maneuvering, it’s less likely to catch and throw the bike off balance.

Hard cases provide much better security from both outright theft and slash-and-grab attacks, are sometimes (but not always) more weatherproof, they sometimes can protect both rider and bike in a spill (as long as the situation described above doesn’t happen, and the luggage or its bracketing doesn’t damage the bike’s frame), and if easily removable can serve as seats or tables. Hard cases are easier to pack, provide better protection for fragile equipment, and can be modified easily with brackets for extra fuel canisters, etc.

Doug Mote's hard cases, ready for "easy going."

Doug Mote's hard cases, ready for "easy going."

Summarizing arguments is easy, but it doesn’t make a choice any easier. What I wondered, and had never seen in any luggage threads except as vague hints, was if there might be a formula that would use easily quantifiable variables specific to the rider to point him or her in the right direction.

My own motorcycle luggage expertise (not counting long ago rides wearing a Camp Trails frame pack, which provided spectacular windage) is limited to the excellent canvas luggage from Andy Strapz, combined with an equally excellent Wolfman duffel, and a Pelican case pressed into service as a security trunk. The combination suited me perfectly, but I wanted to get input from those with far more extensive riding history. So I sent out a poll asking the question: hard or soft, and why? I hoped the results might coalesce into a logical hierarchy that would lead to a simple formula.

Those who shared their experience included Carla King, Tiffany Coates, Lois Pryce, Austin Vince, Doug Mote, Kevan Harder, Nicole Espinosa, Brian DeArmon, and Bruce Douglas. The result comprised what I considered to be a useful cross-section of the long-distance riding community—both sexes, and a mix of body sizes, travel styles, and motorcycle choices (from 250 to 1200 cc).

Indeed, as I began going through the responses from this vast pool of experience, definite trends became apparent. In the end I was able to come up with an algorithm accurate enough that I could plug in variables from almost any of the experienced riders I polled and correctly predict what kind of luggage he or she used in what situation.

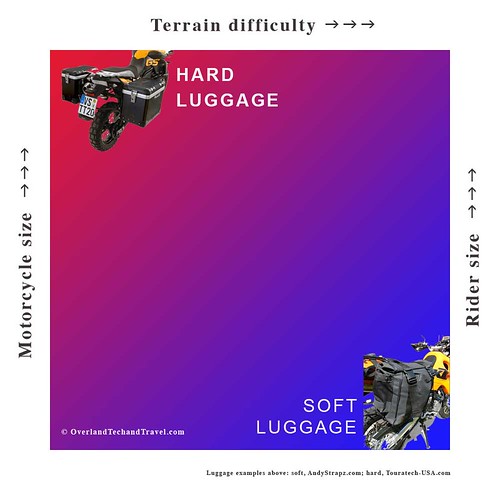

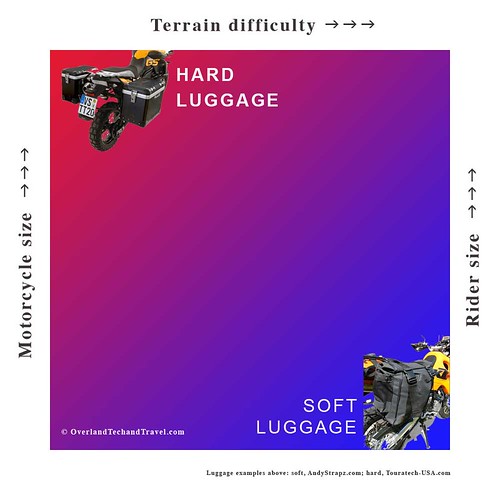

Essentially (aside from your budget), I decided only three variables are necessary to determine which type of luggage will best suit you. While there is some gray area, in general I think most people will find themselves trending one way or the other. The variables are:

- Size of motorcycle

- Size of rider

- Difficulty of terrain

No earth-shaking revelations there, but the relationship between the three can shift things one way or another. The chart shows how the recommended choice shifts from hard (red) to soft (blue), with purple as the could-go-either-way middle ground.

Simply explained, if you’re a big rider on a big bike and stick to asphalt or fairly well-maintained dirt roads, the advantages of hard luggage will most likely outweigh its disadvantages. Conversely, a small rider on a small bike who frequently challenges technically difficult routes would almost certainly be better off with soft luggage.

Some ambiguity arises if we start mixing and matching variables, but the observations of our experts still tilt the smart choice one way or the other. For example, small bikes—say under 650 cc—have a harder time coping with the weight and windage of hard luggage, regardless of terrain. Similarly, a big rider on a big bike who finds himself in central Africa during the rains, or deep in Egypt’s sand seas, or even on three-plus-rated 4x4 trails in the American West, will still benefit from the lighter weight, lower CG, and forgiving impact absorption of soft luggage.

As filmmaker Sterling Noren recently found out, even anodized aluminum cases aren't impregnable

As filmmaker Sterling Noren recently found out, even anodized aluminum cases aren't impregnable

There’s also one more option to be considered regarding hard cases: While the Ewan-endorsed, steamer-trunk-sized aluminum cases represent the paradigm of hard luggage, lighter and smaller plastic cases, such as those offered by BMW for the F 650 GS, represent a viable middle ground in price, weight, and windage (and security). Another increasingly popular approach is to mount a small hard case such as a Pelican as a rack trunk, to provide security for cameras, laptops, and such, and go with soft cases for the rest of the luggage.

Here are some of the comments from our panel of experts, who collectively total a couple of million miles of motorcycle travel, including four circumnavigations.

Carla King’s motorcycle adventures began in 1995 with a 10,000-mile circumnavigation of the U.S. on a Ural with a sidecar, and haven’t stopped since. You can order the delightful book documenting the trip, along with her other published works, from her website here. Carla wrote, “Right now I’m setting up a new-to-me KLR, for which farkle options are famously infinite. After much research into cost, durability, security, convenience, and safety, I chose the Giant Loop soft luggage. Seems I can throw it on any bike, stuff almost any size and shape of thing into it, check it as luggage, and perhaps most importantly it’s not going to crunch my bones when I ride beyond my skill level and fall on (insert hard object here).”

Tiffany Coates set off on her first motorcycle trip, from the U.K. to India, with two months of riding experience. She has a bit more now—over 200,000 miles worth and counting, including the riding she did while filming a BMW unscripted commercial on Thelma, her much loved and well-used BMW R80GS. Tiffany still nurses the factory plastic cases that came on the bike, the latches of one of which long ago gave up trying to hold in the contents (small wonder - see photo below). According to her, “For me, the BMW plastic cases are ideal. Perfect size, with the ‘suitcase compression’ system which means I cram everything in and then sit on it (or two of us if we’re two up). Apparently we get more in these cases than the large metal ones due to the compression. Cheaper and lighter than metal cases and smaller—no risk of getting a leg caught under them if there is a fall. Also ultra-easy to unlock and whisk off the rack ready to carry into a hostel, or for emergency unloading in a river fall! As they are hard cases they are secure as well. I’m not anti-soft luggage, I have just never used it as the BMW panniers were on Thelma when I got her and so I never had a decision to make about what luggage to use.” Find out where Tiffany is now here.

Tiffany and a friend do a little cargo compacting

Tiffany and a friend do a little cargo compacting

Lois Pryce couldn’t seem to exorcise the motorcycle travel bug by riding a 225 cc Suzuki from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego. So she traded up to a much bigger bike (250 cc) and rode from her home in England to Cape Town (two excellent books here). As she was on tour in the Netherlands with her bluegrass band, the Jolenes, when I emailed her, her reply was short but thorough: “I prefer soft luggage: lighter, less ostentatious, no need for a rack, easy to lift on and off, easy to repair, and cheaper to buy. AndyStrapz panniers are the best.” (Want to hear the Jolenes? Go here. Lois is the banjo player.)

Austin Vince’s main claim to fame is that he’s married to Lois Pryce. Oh, well . . . he’s also ridden a Suzuki DR350 around the world. Twice. And made a rousing film of each trip. Austin is the antidote to anyone who tells you you need a $20,000 motorcycle and a further $5,000 in kit to do any serious adventuring. His riding suit is a pair of mechanics’ coveralls. His goggles appear to be Audrey Hepburn’s castoff sunglasses from Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Tent? A surplus shelter half. Luggage? I’ll let Austin explain.

“Soft. Here’s why:

1) Looks cooler and less aggressive compared with armoured-car-ish aluminum boxes. I really do think this is important when travelling amongst poorer societies.

2) Easily personalized and created from government surplus stores, etc. If your luggage is improvised then you are richer in terms of investment in your project. My current ALICE pack system has two major bags of 40 litres each, and 12 separate mini pouchlets of varying smaller volumes, all super-useful: Oil, rags, toilet paper, sun cream, water, etc. is all instantly accessible without undoing a single flap. Total cost, $35 U.S. No manufacturer can match this.

3) Safety. No one has broken a leg on a soft pannier.

4) Luggage is easily repaired and conversely, if it gets damaged, it only cost $35 so who cares?

5) All my DIY luggage is zero waterproof so I simply put my gear in a $5 waterproof liner therein—it’s so simple I want to cry.

6) Hard luggage makes the bike physically massive and far too unwieldy.

7) Jonathan, I love you (call me—like the old times).”

(Editor’s note: I take no responsibility for number 7. Just passing it on in the interest of full disclosure.)

Austin Vince's $35 pannier system (courtesy U.S. government surplus)

Austin Vince's $35 pannier system (courtesy U.S. government surplus)

Brian DeArmon is the thinking rider’s rider. Every equipment choice he makes is the result of not just long experience as a motorcyclist, but extensive research into pros and cons, competing brands, and above all, quality. Generally when Brian adds something to one of his bikes, that’s the last you hear about it, because it works. Given all that, it was no surprise that his detailed response more or less summarized my conclusions before I even reached any.

“Short version: Bigger bikes that are being used on easy to moderate terrain, with predictable weather conditions, I tend to favor hard bags (primarily for the security and ease of access). For small bikes, or any bike going where trail conditions are unknown, I prefer soft bags.

Long version:

Suspension: It’s too easy to overload a small bike already. Add in 15 or 20 pounds for the hard panniers and mounting brackets, you eat into valuable capacity. The big bikes are better able to handle those loads. Unfortunately, hard panniers also make it real easy to strap even more crap on the bike since they typically create a nice big surface area & include those nice tie down points.

Power: Smaller bikes typically don't have the power to push big loads down the road at the speeds required in the west. I've ridden the DR200 on the freeway with no load, and it’s kinda scary, even in the slow lane. I couldn't imagine doing it with an extra 40 pounds of pannier/gear/food/water (state highways and back roads, sure, just not freeways where traffic is moving 70 to 80 mph). Put that load on a GSA or big KTM and you don't have the same problem.

Trail conditions: On relatively tame roads, in known weather conditions, hard panniers are not much of a liability, IMO. The risk of crashing isn't that high. But once conditions become unknown, or weather conditions make a turn towards the wet side (mud), hard panniers become a huge liability. There is the obvious danger of tib/fib breaks, but also damage to the bike itself. My GS has a bent subframe caused by smacking a pannier on a rock. That is hardly a concern with soft bags.

Security and Convenience: Hard bags have a hands-down advantage for security and ease of use. Dump in your gear, close the lid, lock the latch, and you’re done. They’re typically easy to dismount and move into a hotel room, etc. Soft bags often have a convoluted mess of straps that makes it more difficult to access gear and install or remove. Soft bags also need to be checked regularly as loads change and straps loosen. Of course there is also the problem of having nothing between your gear and a thief but a knife.

Basically, I see soft bags as the default luggage system, with hard bags being a legitimate option if certain conditions are met.”

Nicole Espinosa didn’t like the racks available for the Suzukis she rides, so she made her own. Now she runs a business, Rugged Rider, which specializes in high-quality accessories for the reliable and overachieving small DRZs. Nicole wrote: “I feel the DRZ400 is the perfect bike to set up for adventure. It has a strong enough engine to maintain a comfortable 70 MPH on the highway, and is a nimble enough size to have fun on tight single-track fully loaded. That said, I prefer soft luggage for a tighter profile on highway against wind, and on trails for width. I only keep my clothes and rain gear in my Ortleib dry side bags, and have only traveled in North America as of yet, so I haven’t put the security of soft bags to the test internationally. I keep my expensive gear in my tank bag that I can carry with me or ratchet down on my locking combo luggage rack.”

All you need to know about Doug Mote as a rider is summed up below in his reference to “easy going.” Anything else I’d add would be superfluous, except to say he’s one of the nicest guys I know (despite his comment about kicking KTM ass). As a lumberjack and body double for Paul Bunyan, Doug was at the far end of my bell curve for big riders with big bikes. He sent: “I have hard and soft luggage, and use both. My preference depends on itinerary. For easy going, like say a run to Prudhoe Bay on a schedule, hard bags offer several advantages, not the least of which is better weather protection. On this type of good road trip in wide open spaces, there is little risk of leg or foot injury such as I have witnessed friends incurring when trapped between bag and earth. For tough going, where lightness and flexibility are key, soft luggage is superior. Spills are not so risky, and my entire kit weighs less than empty hard bags with mounting racks. I use only soft bags on the 650, either soft or hard with the 1150 depending on the route and how much KTM ass there is to kick. For extended travel with diverse route conditions, soft luggage is my clear choice."

I won’t claim that Bruce Douglas sometimes uncovers a motorcycle in his yard he’s forgotten he owns, but he does own a lot of them, and has based his transportation on motorcycles since his very first vehicle, a two-stroke Yamaha 360. His main backroad bike is a thoughtfully modified Suzuki DR650. Bruce wrote: “I’d say hard cases for security, appearance, and good mounting surface for other stuff. I think they’d be fine if I knew I wouldn’t be riding through any difficult terrain, but if there was a chance I might go down I’d have to go with soft bags. A few times when I’ve put my foot down while moving on the TransAlp I had it get caught under the hard case. It was clear how easily you could break something—and it wouldn’t be the case. I think I’m sold on soft bags now after the Baja trip. I like their versatility; I can use different bags with my mounts, since the main function of most mounts is to keep the bags away from the rear wheel. I’m happy with what I have, they’re simple and straight forward. The Wolfman Gen 2 mounts are interesting: a little complicated but they add more mounting points, and a means to carry extra fuel. Also knowing I can repair them with a sail needle and thread is nice. In a spill they flex, rather than dent. If the mounting straps tear off you can come up with a repair, or just tie it on with cord. The chance of the mounts coming out of hard cases is slim, but if they did, a field repair would be difficult. Soft bags aren’t as secure, but after undoing a few straps you can pull them off as saddle bags and carry them over your shoulder (a la John Wayne). In Baja I was able to carry all my gear in one trip: saddle bags on my shoulder, the tail bag in one hand, and whatever in the other hand. Soft bags also make you think about packing and not be tempted to just dump stuff into metal boxes.”

And finally, from Kevan Harder, a California police and SWAT officer who also works for RawHyde Adventures, where it often seems motorcycles are defined as BMW or . . . everything else . . . comes a firm vote for the red corner of the chart: “I strongly recommend hard bags for durability, protection of gear, and versatility (bike service stand, chair, table, etc).”

So there you have it, courtesy of some of the most experienced riders on the planet: an easy way to determine what type of motorcycle luggage will best suit you, your bike, and your riding.

Think this will end all those forum debates?