A few years ago on a long road trip, Roseann and I opted for convenience over our usual preference for solitude, and stopped for the night in a developed campground: picnic tables, barbecues, flat sites, perfectly symmetrical pine trees—actually quite nice as such places go. That evening an enormous motorhome inched carefully into a nearby slot. The driver emerged just long enough to open a side panel and pull out a remarkably colon-like corrugated hose, which he plugged into his deluxe site’s sewage receptacle. Another umbilical fed electricity to the behemoth. The man then scurried back inside, and soon I heard the sound of some TV program on what I assumed had to be at least a 40-inch flatscreen. And that was the last we saw of either him or his wife.

I try not to judge fellow travelers on the size or splendor of their vehicles. After all, to someone in a CJ5 with a Eureka A-frame tent our Four Wheel Camper must seem pretty posh. But, while the camper provides us a cozy, stormproof home away from home, holing up inside is not the goal when we’re traveling—even in Jellystone Park. In good weather we like to be outside as much as possible. With the camper’s excellent Fiamma awning deployed, and a table and chairs set up, we can lay out snacks and drinks, then tackle some weighty biological issue like seeing how many bird species we can document while sitting down. “Nine species in one martini!” Roseann is likely to announce (although identification skills wane somewhat after the second, and we're likely to record birds never seen in this hemisphere . . .).

Where was I? Right: Until recently we relied for our outdoor table on one of those ubiquitous roll-up blue-vinyl-covered things with the screw-in aluminum legs. It was ugly and wobbly, but perversely durable despite my best attempts to “accidentally” destroy it. A Maasai shuka used as a tablecloth improved its looks immeasurably, but I still knew what was underneath . . .

Then, a few months ago, Roseann emailed me (from across the room) a link to the Front Runner camp table, designed to slot under the company’s roof rack. We'd used a version of it in Tanzania and Kenya several times and had been very impressed. Here was a proper outdoor table: welded and braced aluminum legs that folded flat under a top formed and welded from a single sheet of stainless steel. At 29 by 45 inches, the table was large enough for food prep, eating (it seats four snugly), or work, and it weighed a reasonable 23 pounds. She also linked to the Z brackets designed to attach to the Front Runner rack—and then asked, “Could we mount this under the front overhang of the camper?”

I emailed back, “Great idea,” then did some measuring on the camper—plenty of room. Tom at FWC said no problem drilling the composite sheet that forms the bed area of the camper as long as I sealed it well, and certainly no problem with the extra weight: the FWC’s overhang is tested to 1,100 pounds (or, as he and I quipped at the exact same time, “Two average Americans.”).

The table's top is formed, welded at the corners, and riveted to the aluminum frame.

The table's top is formed, welded at the corners, and riveted to the aluminum frame.

When the table arrived it met my expectations and then some. Compared to its cheesy roll-up predecessor it was the Rock of Gibraltar. All the hardware was cadmium-plated and secured with nylocks. The stainless top would be impervious to spills or heat. True, at $285 such features should be taken for granted. Nevertheless it was a relief to consign the blue vinyl table to the Cemetery of Obsolete but Kept Around Forever Camping Gear down in the storeroom.

Exercising due measure-thrice-cut-once caution, I marked and drilled, then veeery carefully countersunk (so the bed’s top section could slide over the bolt heads) three holes for each of the Front Runner Z-brackets from inside the camper. They are designed to hold the table on its narrow ends, but I needed them to hold it on the longer sides, meaning the table would protrude about a half a foot each way.

The bolt heads are countersunk just enough to allow the bed extender to slide over them.

The bolt heads are countersunk just enough to allow the bed extender to slide over them.

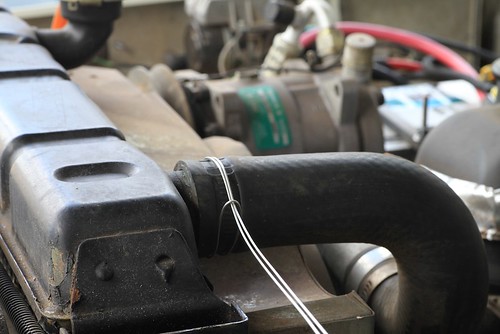

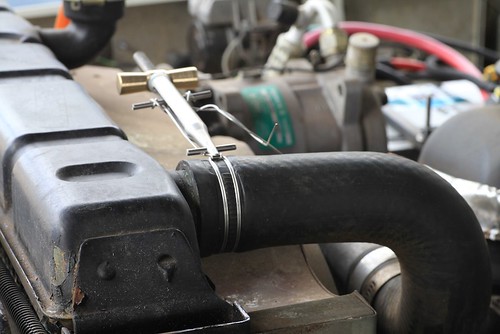

The latch mechanism included with the brackets wouldn’t work in our application, so I used a 24-inch-long piece of 1.25-inch aluminum angle iron as an end stop on the passenger side of the truck. I drilled two holes sideways through the frame and top of the table, and inserted a pair of two-inch-long 1/4-inch-diameter clevis pins through them. A pair of hairpin clips holds the pins to the table:

The pins extend through two holes in the end bracket and are secured with two more hairpin clips backed by a rubber washer and a metal washer. I also glued a couple of furniture bumpers on the back of the end bracket, and two flat pieces of rubber gasket on the insides of the Z brackets where the table slides in from the driver’s side of the truck.

The Z brackets came with carpet strips glued along the bottom, so I hoped all the rubber and carpet would minimize any rattling directly over our heads. My last step was to install a backup latch at the other end, using two of the cunning little Expeditionware Transport Loops sold by Expedition Exchange, plus a Quicklink. (My plan is to try to find a small padlock that will fit through these loops.)

Twelve hours after I finished up, the installation got a good test when we left for a biological survey in the Sierra Aconchi in Mexico, which involved a 230-mile paved approach, then a rough ten-mile climb up a four-wheel-drive trail. On the highway the table created no noise at all. On rough slow pavement with the windows open we could very infrequently hear a barely perceptible oilcan effect over sharp bumps as the table top flexed. On the trail there was zero sound from the table or mount, at least none we could hear over the tire and drivetrain noise.

The completed bracket assembly.

The completed bracket assembly.

Once in camp the table proved just about perfect. There was plenty of room to spread out plant samples, notebooks, bird guides, and binoculars; at a group dinner we covered it with chips and salsa and vegetables, then served the outstanding pizzas Roseann somehow managed to make on the camper’s stove top. One night delivered a torrential rain which bothered the table’s aluminum and stainless steel not at all. Total time to set it up on the first day and stow it on our last morning: about two minutes each.

So, not only did we gain a big upgrade in the quality of our outdoor table, we also gained storage space inside the truck. If you have an overhead camper—or a roof rack—I can recommend the Front Runner approach.

On the other hand, if you have a fondness for blue vinyl, email me.

Addendum: A forum member on Wander the West suggested that the Front Runner brackets could be set up to carry a solar panel in the same spot. Brilliant.

Equipt Expedition Outfitters also carries similar tables from K9 racks, in three sizes.

Front Runner Outfitters is here.

The Transport Loops are available here.

Pockets galore! (on the Altiplano in Peru)

Pockets galore! (on the Altiplano in Peru) Latitude 0 (at the Equator in Ecuador)

Latitude 0 (at the Equator in Ecuador)