If you're not familiar with him, his work—and his well-used vehicles—this interview on the Leisure Wheels site with Dr. Flip Stander, who studies desert lions in the Namib, is well worth the read. A donation would be well worth it, too. No, your eyes aren't deceiving you: That is a Toyota Hilux in the photo above, with a Land Rover roof and windshield Siamesed on top. Stander put over 750,000 kilometers on it before the South African Land Cruiser Club donated a Land Cruiser to his project.

The first "adventure trailer" and "earth cruiser?"

If you know anything about T.E. Lawrence you are aware of Lowell Thomas (and vice versa, I suppose). Thomas, the indefatigable journalist and travelogue producer, was nearly single-handedly responsible for making "Lawrence of Arabia" a worldwide legend through his sensational traveling multimedia show, With Allenby in Palestine and Lawrence in Arabia, seen by over four million people in the years following World War I.

Lawrence and Thomas in Arabia

(Ironically, it almost never happened. Thomas was originally scheduled to cover the Great War in Europe to drum up support for the potential entry of the U.S. into the conflict. When it became obvious that trying to romanticize the gruesome quagmire that was the Western Front would be futile, he looked for a more promising theater, and thus landed in the Middle East.)

After the success of the Lawrence show, Thomas went on to star in and narrate innumerable other travelogues, of which one is this nine-minute 1940 production, Royal Araby. My friend Bruce sent me the link after he spotted one of the spectacular armored Rolls Royces employed with great effectiveness by Lawrence during the war, this one still in service years later. Indeed at about 2:38 you'll spot the turreted vehicle front and center. (See here for an account of one of Lawrence's unarmored Rolls Royce cars, and the impressive bodge repair he managed under enemy fire.)

But something else caught my attention: two of the vehicles used by the Thomas expedition. One, an American sedan, is towing what could easily be taken for any number of the modern "adventure trailers" so popular with overlanders. Behind that is a behemoth of some sort of articulated truck with what would seem to be spacious living quarters in the back section.

I must try to find out more.

Check it out on YouTube, here.

The sky didn't fall after all . . .

A scant and diminishing few of you reading this might recall the dark days of the early and mid 1970s—dark at least for automotive enthusiasts, who were convinced that the seven-decade-long history of increasingly interesting—and fast—automobiles was over forever, thanks to OPEC embargoes and the rising influence of commie environmentalists who thought all Americans should have access to clean air and water. Executives from the Big Three stood before Congress and swore they would go bankrupt if forced to install catalytic converters on their vehicles. In 1975 a base Chevrolet Corvette’s 350 cubic-inch V8 produced a wheezing 165 horsepower, and the venerable MGB was choked down to 68—exactly the same as a 750cc Honda motorcycle of the day.

Not all manufacturers simply wrung their hands and complained. Honda produced its CVCC (Compound Vortex Controlled Combustion) four cylinder engine for the Civic, which handily met all proposed pollution requirements without a catalytic converter. When the CEO of GM sneeringly dismissed the technology as suitable for “a toy motorcycle engine,” Soichiro Honda bought a Chevy Impala and had it flown to Japan, where his engineers designed, built, and installed CVCC cylinder heads on its V8, then flew it back to Michigan—where it passed EPA requirements without a catalytic converter. GM’s CEO immediately apologized and asked to license the technology. Actually he did neither.

In any case, aside from a few bright spots (Porsche managed to retain much of the 911’s performance by adding engine capacity and keeping weight down, not to mention introducing the Turbo version), the future looked bleak.

For truck buyers the situation was similar. Although emphasis on 0 to 60 times was minimal, fuel economy was an issue, with single-digit averages commonplace (actually single-digit averages had been comonplace all along, but with gas prices skyrocketing from 30 cents per gallon to 80, it started to hurt).

I was reminded of all this when I came upon an image of a road test of a Chevrolet C-10 pickup from a 1974 edition of Pickup, Van, and 4WD magazine. The truck’s 350-cubic-inch V8 produced just 145 horsepower and a surprisingly meager 250 lb-ft of torque (torque was generally less affected by pollution controls than horsepower, but apparently not in this engine). The truck took 12.6 seconds to accelerate from 0 to 60 mph with a three-speed automatic transmission, and averaged a wince-inducing 9.8 mpg in “normal driving.” Also, astonishingly, the weight capacity on the tested model was only 760 pounds including passengers (although options could boost that to 1,360). And this was a two-wheel-drive truck.

How far we have come, and how silly seem the predictions that reducing pollution spelled the death of performance. Consider the 2016 Chevrolet Silverado Crew Cab tested by Car and Driver. Its 5.3-liter (325 cubic-inch) V8 produces 355 horsepower—well above the one horsepower per cubic inch figure that was the Holy Grail in (completely unregulated) 60s muscle cars—and 383 lb-ft of torque. With an eight-speed auto it propels the truck to 60 in just 7.2 seconds (quicker than that 1975 Corvette), yet the testers saw 15 mpg in normal driving. (Other half-ton trucks are now achieving significantly higher fuel economy figures; I cited this review because its subject was the closest I could find quickly to a direct descendant of that C-10.) This on a four-wheel-drive truck capable of hauling 2,130 pounds and towing over 10,000. Need I add that it produces a fraction of the pollutants that ’74 truck did? And is vastly more comfortable and safe?

The Wescotts return from The Silk Road

One day in the summer of 1993 Roseann and I were sitting in a café in the Canadian Inuit village of Tuktoyaktuk, 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle. We’d been having one of those time-warp conversations with a phlegmatic local whale hunter: He’d ask a question such as, “Where you from?” We’d answer, there’d be a two-minute silence, then, “How’d you get down the river?” We’d answer, then ask him a question: “Lived here long?” Two minutes, then, “Born here.” We were in no hurry, having just paddled sea kayaks 120 miles to get there, so it was a fun way to pass time and—slowly—learn something of the area.

After a while a couple came in—anglos, surprisingly, the first we’d seen since landing the day before. They sat nearby and said hello, and we struck up a conversation that must have seemed alarmingly hasty to the Ent-like whale hunter. They asked how we’d got to Tuk, and when we described our trip expressed open-mouthed admiration. They’d flown from Inuvik, it developed, and had left their pickup and camper there.

And as soon as they mentioned a truck and camper, I realized that the couple was Gary and Monika Wescott. It was my turn to be open-mouthed, as I’d been reading tales from the Turtle Expedition in Four Wheeler magazine for, what, 15 years already by then? I’d devoured the articles documenting the extensive modifications to their Land Rover 109 during the 1970s, had been disappointed but intrigued when they switched to a Chevy truck (which, even more intriguingly, vanished without comment soon after), and then followed the buildup of the Ford F350 that would prove to be the first of a series. Our Toyota pickup had a Wildernest camper on it at the time, but we were saving to buy a Four Wheel Camper of the same type that sat on the F350 Turtle II. Most recently, I’d read along as the Turtle Expedition completed an epic 18-month exploration of South America.

We saw each other over the next couple of days as we all took in the annual Arctic Games, watching harpoon-throwing contests and blanket tossing, and snacking on muktuk. Then we lost touch for 15 years (while they journeyed across Russia and Europe), until reconnecting when I edited Overland Journal.

Since 2009 the Wescotts have been regular instructors and exhibitors at the Overland Expo—until 2013, when they embarked from the show on their latest adventure, a two-year trans-Eurasian odyssey along the Silk Road.

Now we’re delighted to welcome Gary and Monika back from their journey. They will be giving presentations and taking part in roundtables at Overland Expo WEST 2015. Don’t miss a chance to meet these two personable and friendly travelers. Listening and watching as the Wescotts describe their journeys is both entertaining and inspiring, and their latest journey should be fertile ground for good tales.

Best of all, Gary and Monika are genuinely excited to share; there’s not a trace of bravado between them, despite being among the most-accomplished overlanders in the world (and still traveling). They travel because they are passionate about exploring and learning and sharing, not because they are trying to count coup or gain fame. It’s refreshing, and we are glad to have them back.

- Regional Q&A: Russia, Mongolia & Southeast Asia; Friday 2pm

- Regional Q&A: Europe, Eastern Europe & Iceland; Saturday 8am

- The Silk Road; Saturday 11am

- Experts Panel: Top Travel Tips; Saturday 1pm

Explore 40 years of adventures with the Turtle Expedition at http://turtleexpedition.com

From Ethiopia to Arizona—two travelers meet again

The Overland Expo has developed a reputation for bringing people together—both those making new friends and those reuniting with old ones. However, few such stories we’ve heard match this one from Mario Donovan, of AT Overland, who ran into an acquaintance at the 2014 Overland Expo WEST he last met 40 years previously . . . and 8,000 miles away.

"I was a teenager growing up in Ethiopia in the 1970s. At the time my mother worked for the Ethiopian Ministry of Tourism as a publication consultant. Many a traveler, hitchhiker and overlander came through her office, and sometimes they’d end up crashing on the floor of our apartment. I was maybe fourteen or fifteen at the time, and at the height of adolescent reverie. I lusted over motorcycles every waking moment, even more than girls.

I remember my mom introducing me to a British fellow who was on hiatus from his journalism job so he could ride around the world on his motorcycle and write about it. It was a super cool bike because it was a twin, not a single-cylinder as most of the bikes were there. What a dream of independence and freedom for a young man. At the time I was still without my driver’s license, but learning how to pop wheelies on my friend’s bike, and occasionally hot-wiring my neighbor’s bike when he was out of town.

Although I only met the British rider briefly, I thought he was stud for doing what he was doing. Then, maybe five years ago, I read Ted Simon’s book Jupiter’s Travels, and when I got to the short section about his time in Ethiopia it hit me: That was the guy! Not much of a story but a happy coincidence—the Kevin Bacon thing. When I shared it with Ted he seemed rather moved by it, and I was honored to have met him again nearly 40 years later—and to share a drink with him no less!"

Irreducible imperfection: The flimsy

At the beginning of the North Africa Campaign in WWII, the British faced a logistics problem on a scale they’d never imagined. In this, the first totally mechanized war, the need for fuel staggered existing supply lines—and existing supply containers. For several decades the British military had made do with a squarish four-gallon soldered-tin can known officially as a POW can—for Petrol, Oil, and Water—to move the bulk of its petrol supplies. The four-gallon size was light enough to be handled by one man (unlike the common 55-gallon drum), and small enough to be transported by light truck or even motorcycle.

But as General Wavell in Cairo mustered his tanks, trucks, and airplanes to counter the forces of the Italians and Germans massing in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (now Libya), the deficiencies of the POW can quickly became all too clear. Stacked in pallets on cargo ships, the weight of the top layers simply crushed those below, resulting in fuel losses of up to 40 percent, and making unloading the intact containers extremely hazardous with thousands of gallons of petrol sloshing around in the bilges and the fumes powerful enough to render seamen unconscious, not to mention the danger of fire or explosion.

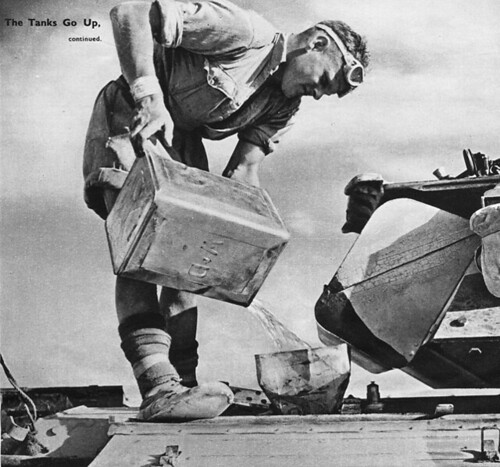

A British soldier refuels a Crusader tank from a flimsy. The funnel appears to have been made from another flimsy.

A British soldier refuels a Crusader tank from a flimsy. The funnel appears to have been made from another flimsy.

Even in smaller shipments the can proved absurdly fragile. Truck transport over 100 miles of desert track frequently left 20 to 30 percent of the contents cascading out the tailgate. In his book The Desert War, Alan Moorehead wrote, “The great bulk of the British Army was forced to stick to the old flimsy four gallon container, the majority were only used once. We could put a couple of petrol cans in the back of a truck, two hours of bumping over desert rocks usually produced a suspicious smell. Sure enough we would find both cans had leaked.”

That adjective, “flimsy,” quickly became a noun, and the POW can became universally known as the flimsy, reviled by troops and brass alike. To get an idea of the numbers used, consider that a single Wellington bomber flying a single nine-hour sortie needed 270 flimsies to fill its tanks. Piles of empty containers 30 feet high stood outside every airbase, and littered the Western Desert wherever British vehicles ranged.

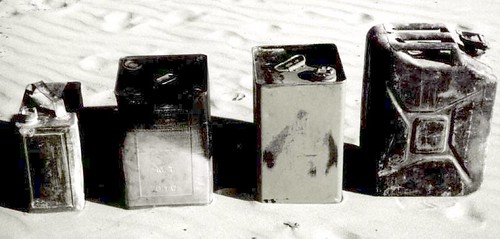

Fortunately, an alternative presented itself when the retreating German Army began abandoning its own 20-liter containers. These were of embarrassingly brilliant design—perimeter-welded of stout steel for strength, with a three-handle configuration that allowed one man to carry two empty cans with one hand (or two full cans if he was strong), and which facilitated effortless hand-off of full cans down a line of men. The leak-proof cap was secured with a fast and foolproof lever, a breather allowed fast pouring, and a clever air trap at the top meant that a full can of petrol would float in water. The British scrounged all the “jerry cans” they could, and in England the design was unashamedly copied to the last detail—two million of them would be sent to North Africa before the end of the campaign. (The U.S. copied the design as well, but substituted cost-saving—and inferior—rolled seams and a screw top that was difficult to seal.)

A British two-gallon container, early and later "improved" four-gallon flimsies, and the vastly superior German 20-liter fuel can. Note the thin and awkward handle of the flimsy.In the meantime, the flimsy proved happily more useful as a makeshift device than it did in its primary role. Filled with sand, it became an impromptu building block for gun emplacements and buildings. Cut in half and filled with petrol-soaked sand, it was used as a stove for boiling water (in another half-flimsy), and known as a Benghazi burner or Benghazi boiler (the latter term was subsequently applied to the Thermette, an early volcano kettle supplied to troops from New Zealand).

A British two-gallon container, early and later "improved" four-gallon flimsies, and the vastly superior German 20-liter fuel can. Note the thin and awkward handle of the flimsy.In the meantime, the flimsy proved happily more useful as a makeshift device than it did in its primary role. Filled with sand, it became an impromptu building block for gun emplacements and buildings. Cut in half and filled with petrol-soaked sand, it was used as a stove for boiling water (in another half-flimsy), and known as a Benghazi burner or Benghazi boiler (the latter term was subsequently applied to the Thermette, an early volcano kettle supplied to troops from New Zealand).

The Benghazi burner was also effective for illuminating rough landing strips at night—and that was quite possibly the role played by the crudely bisected Shell example we found in Egypt’s Western Desert this February (top photo). It speaks to the extreme aridity of this eastern edge of the Sahara that after 70 years even something as thin as a flimsy was still in recognizable shape.

Historic bodge fixes: T.E. Lawrence

T.E. Lawrence, on right, enters Damascus in the Blue Mist.

T.E. Lawrence, on right, enters Damascus in the Blue Mist.

Here’s a bit of history David Lean left out of his epic film Lawrence of Arabia: In addition to the camels T.E. Lawrence and his Bedouin allies used on their spectacular raids against Turkish outposts and railroads in what is now Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Syria, Lawrence employed a fleet of automobiles.

An unabashed romantic, Lawrence was nevertheless also an utterly practical (and brilliant) military strategist, despite having no training whatsoever beyond the written accounts of historic campaigns he had devoured since childhood. He was the first battlefield commander to recognize and fully exploit the value of aircraft used in support of ground troops, and he pioneered aerial mapping techniques. His guerrilla tactics are still studied today by insurgents as well as counterinsurgents, yet at Tafileh in January of 1918 he proved himself equally capable of commanding a pitched conventional battle.

Lawrence also quickly realized that on the wide, flat deserts he had to cross with heavy loads of explosives and weapons, an automobile could cover ground much faster than a camel. After his stunning victory at Aqaba, he had the clout to request and receive a small detachment of armored cars, accompanied by automobile “tenders.”

But these weren’t just any automobiles. Lawrence’s desert raiding machines comprised nine Rolls Royce 40/50 Silver Ghost motorcars, including a personal vehicle he named the Blue Mist.

At the beginning of the war, Rolls Royce was already established as a maker of the finest automobiles, catering to the upper crust of society. But in those early days, such a reputation had as much to do with reliability and durability as it did luxury. In 1907 the company had entered one of its 40/50-horsepower models in the grueling Scottish Reliability Trials, and followed up the performance by driving the same car between London and Glasgow—27 times. The Autocar magazine declared it “the best car in the world”—still Rolls Royce’s motto a century later.

A Rolls Royce 40/50 Silver Ghost in more genteel surroundings. (Image courtesy www.ritzsite.nl)

A Rolls Royce 40/50 Silver Ghost in more genteel surroundings. (Image courtesy www.ritzsite.nl)

That tremendous strength served Lawrence well in terrain and conditions far removed from what even Henry Royce had envisioned. In one passage from Seven Pillars of Wisdom Lawrence describes an exploratory excursion: “Their speedometers touched 65 mph; not bad for cars which had been months ploughing the desert with only such running repairs as the drivers had time and tools to give them.”

Alas, even the mighty Rolls Royce proved not completely immune to damage from constant, crushing abuse.

On September 16, 1917, Lawrence and a small team set out to demolish a railway bridge south of Amman, in what is now Jordan. The Blue Mist was “crammed to the gunwale” with explosives and detonators. While his companions, who had followed in another tender, engaged the Turkish post guarding the bridge in a brief but ferocious firefight, Lawrence coolly placed 150 pounds of charges in the bridge’s support spans, ignoring desperate signals from the two British officers supervising the cover fire that Turkish reinforcements were on the way. The explosion sent twisted shards of the bridge plunging into the ravine below, and further enraged the pursuing Turks.

And at that moment, as the group raced away from the rising smoke, one of the Blue Mist’s rear spring brackets snapped, dropping the body onto the tire and instantly halting forward progress. It was, as Lawrence later described it, the first and only time a Rolls let him down in the desert.

Anyone else would have simply abandoned the car, but Lawrence was loath to lose not only his faithful Blue Mist (“A Rolls in the desert was above rubies,” he wrote), but the extensive explosives kit inside. With the Turks perhaps ten minutes away, he and his driver (who was nicknamed “Rolls”) jacked up the car, and untied a length of wood plank kept with each car for deep sand recovery, with the idea of wedging it between the axle and chassis. It was too long, and “Rolls” estimated they’d need three thicknesses of the wood to support the car. They had no saw, but Lawrence solved the problem by simply shooting crosswise with his pistol through the plank several times in two places, until the board broke in three pieces. The Turks heard the firing and paused their pursuit, which lent Lawrence and “Rolls” time to rope the planks in place, using the running board as a mounting point, and make good their escape. Lawrence wrote:

“So enduring was the running board that we did the ordinary work with the car for the next three weeks, and took her so into Damascus at the end. Great was Rolls, and great was Royce! They were worth hundreds of men to us in these deserts.”

So, if you don’t already have them on board your own Rolls Royce, I suggest adding to your recovery kit one (1) wooden plank and one (1) pistol.