In March this year I embarked on a yearlong project exploring the chroma—colors, from Greek khrōma for “surface of the body, skin, color of the skin”—of the Sonoran Desert by creating paint and ink from 10 plants and soil types of our region.

Some of the colors will be relatively easy to capture—ink from the magenta fruit of the prickly pear cactus—while others will involve expedition-level travel—using scientific survey reports to track down the elusive Mayo indigo plant, popular throughout the Americas as a treasured blue paint and dye.

Each color tells a story of culture and nature: purple ochre, a hematite (iron oxide) pigment formed through the fires of volcanic upheaval, was popular amongst the southwestern Trincheras Culture (A.D. 700-1100) and traded widely, where did it originate? My research has found one of the sources, in Tucson, near Tumamoc Hill, site of a Trincheras outpost (see below).

Tucson Mts. purple ochre (aka hematite)

Examples of Trincheras pottery from northern Sonora, Mexico (Douglas R. Mitchell, Jonathan B. Mabry, Natalia Martínez Tagüeña, Gary Huckleberry, Richard C. Brusca & M. Steven Shackley (2020) Prehistoric Adaptation, Identity, and Interaction Along the Northern Gulf of California, California Archaeology, 12:2, 163-195, DOI: 10.1080/1947461X.2020.1818938 )

For each color I will create an ink or a paint, and works of art as well as written stories of nature and culture—“the chroma, or skin of the place”—which will be compiled in a finished work, a book, and gallery show: Chroma Sonorensis.

CHROMA 1: the jaguar and the Ochres

Iron (Fe) is the fourth most abundant element, by mass, in the Earth’s crust. As it ages in the soil, the iron oxidizes (a process in which a substance morphs because of the addition of oxygen—think rust) and changes colors. There are yellow, brown, red, purple, and even green iron oxides, also known as “ochres.” The differences in their hues are a matter of what the base mineral or minerals are and how much moisture was involved in their formation. For example yellow ochre is FeO(OH)·nH2O, a hydrated iron (limonite), while red ochre is Fe2O3 and gains its red from the mineral hematite, which is an anhydrous (un-hydrated) iron oxide. Purple ochre is the same formula as red but comprises different particle-size and light-diffraction properties.

Humans have been using ochres to paint cave walls, adorn their bodies, and decorate objects for more than 200,000 years. Archaeologist Tammy Hodgskiss wrote:

“People may say ochre is the earliest form of art and symbolism, but there’s more to it. Ochre shows how our brains were developing, and that we were using our environment. It bridges the divide between art and science.”

Ochres are still used today, as pottery slips and in paint: yellow ochre, burnt sienna, raw umber, vivianite, and many others.

And let’s not forget that human bodies—as with many animals—contain iron, 70% of which is carried in our blood via hemoglobin, which transports oxygen from lungs, gills, or other respiratory organs to peripheral tissues that need the oxygen for metabolism. When the hemes pick up oxygen molecules, the interaction (oxidation) turns the blood red.

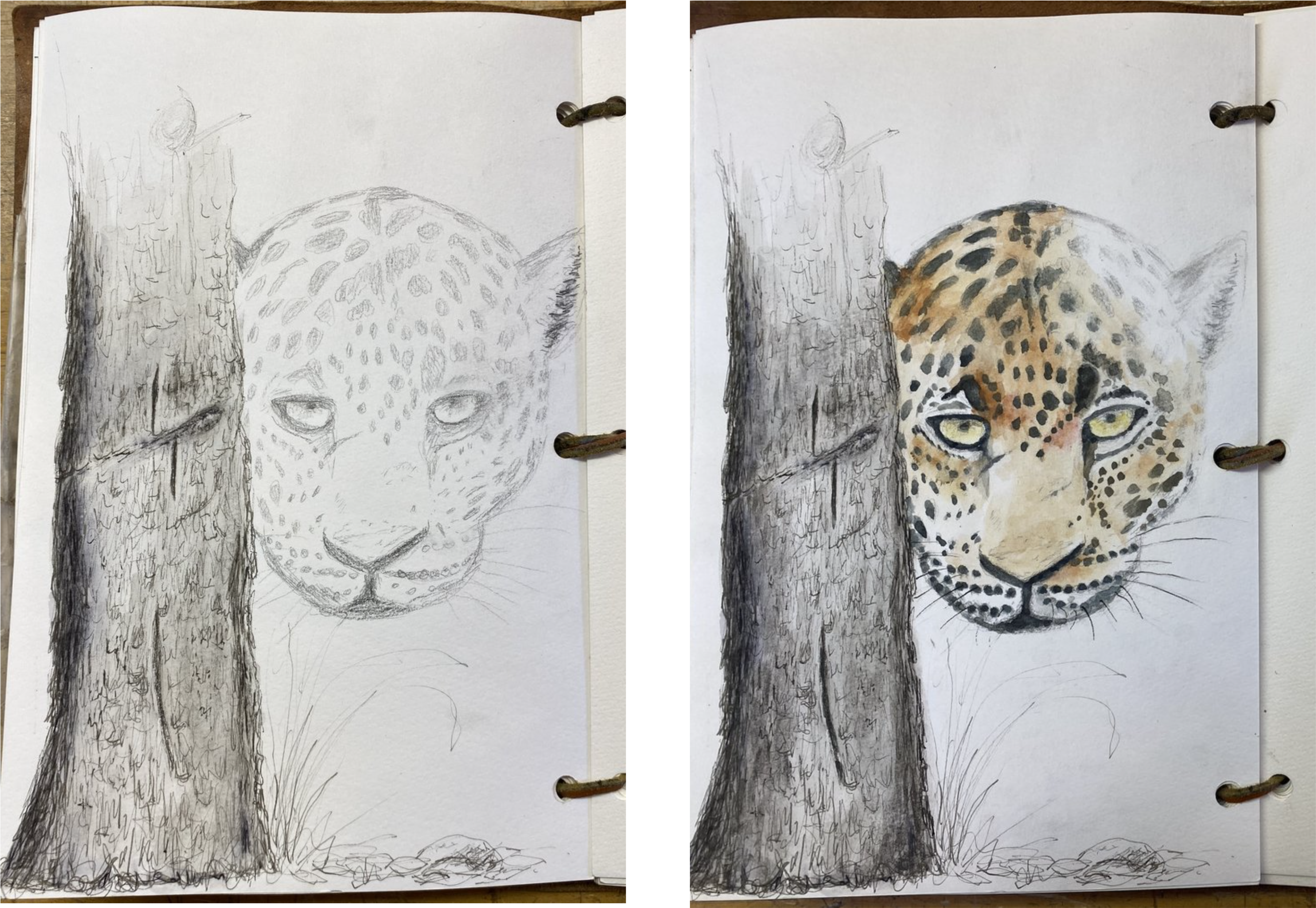

I knew I wanted to include an ochre chapter in Chroma Sonorensis, and immediately thought of the similarities between the beautiful red and orange ochre cliffs so common in the desert Southwest with the colors of a jaguar’s pelt. Southern Arizona and northern Mexico are home to a handful of the northernmost jaguars on the planet. And there is no more famous jaguar in the Sonoran Desert than the male called Macho B, who was was snared in 2009 in a leg-hold trap by Arizona Game and Fish Department biologists so they could radio-collar him. The capture was ill-conceived (it was clandestine not to mention illegal to handle an endangered species and stupid to do so to a 14+ year old big cat) and poorly executed (he was given too much tranquilizer) and led to the death of this magnificent creature.

And so I decided to honor Macho B by making a pilgrimage to the tree where he was snared, hopefully collect pigments from the site, and paint his portrait with the wild paint gathered from where his own iron-rich blood was spilled—telling his story, keeping it alive so we may prevent this from happening again.

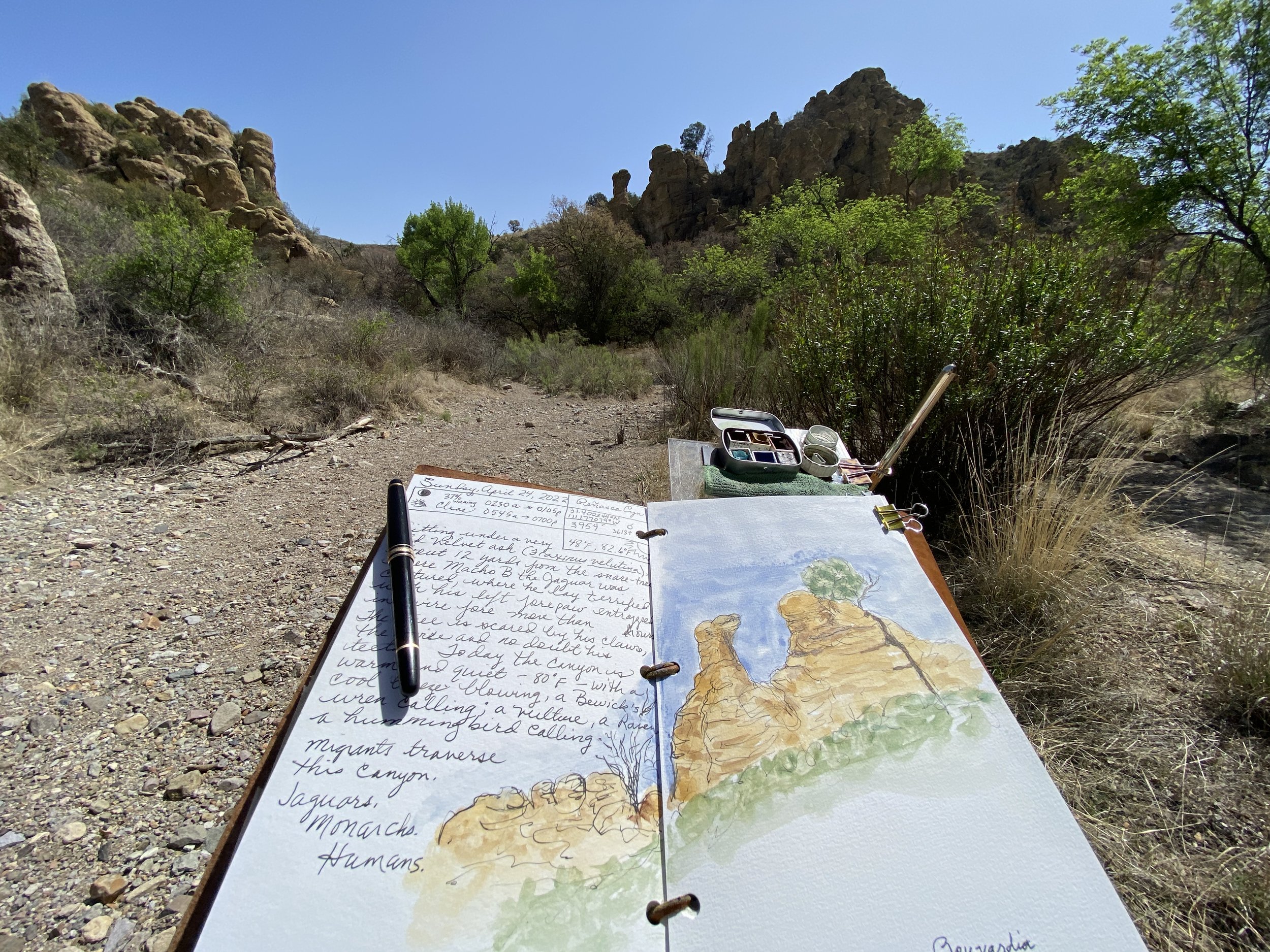

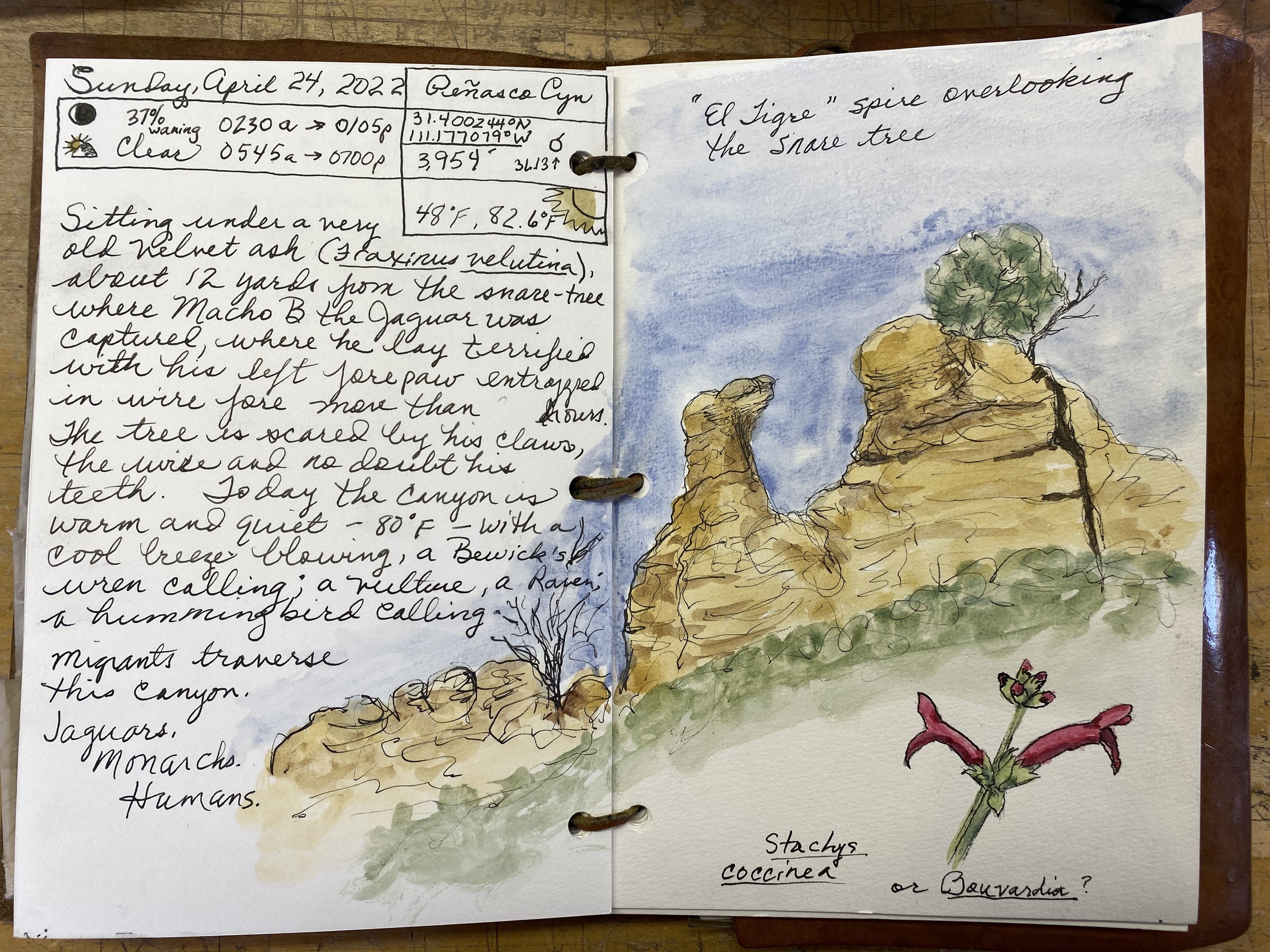

Heading into the yellow-ochre walls of Peñasco Canyon near the Mexico border.

In late April my husband Jonathan Hanson and I followed a rough four-wheel-drive track into the rugged canyon country of southern Arizona's borderlands, west of Nogales. The yellow-ochre hoodoo-spires of Peñasco Canyon greeted us as we hiked to the snare tree site.

This pilgrimage and project are very personal for me and Jonathan because we heard Macho B roaring in Brown Canyon in the Baboquivari Mountains in 1997, just weeks after he was first photographed on the ridge to the north of our house. I have the field note in my nature journal about it.

The tragedy of the snare is that not only was capturing and radio collaring not necessary—by 2009 he'd been non-invasively studied by trail cameras and scat studies for nearly a decade, and leg-hold snares are notoriously dangerous (two jaguars had already died in Sonora, Mexico, in these insidious traps ostensibly for “science”)—but after the Game and Fish researchers tranquilized him and put on the collar, a few days later he stopped moving. They found him in very bad health, airlifted him to Phoenix, and euthanized him.

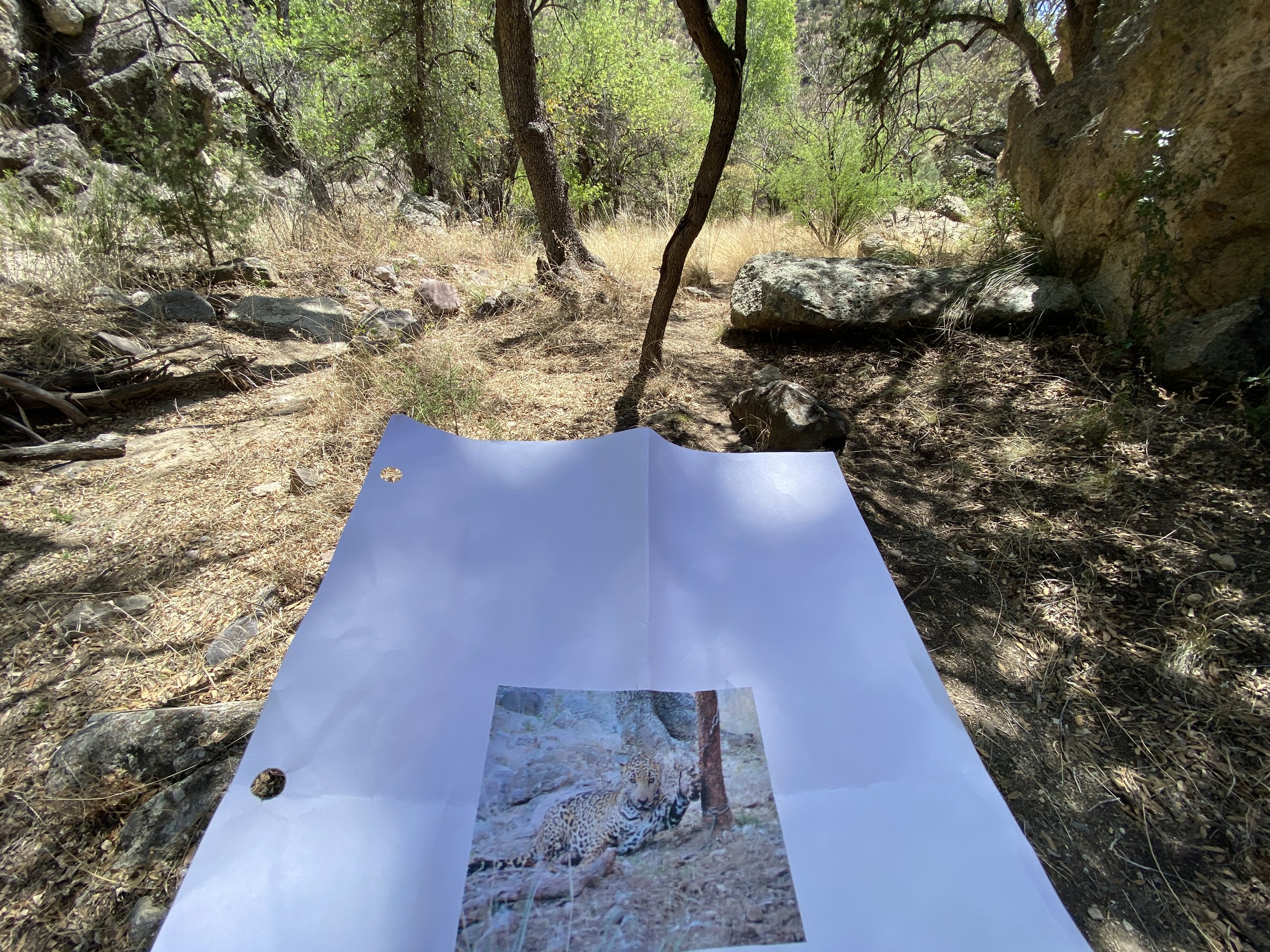

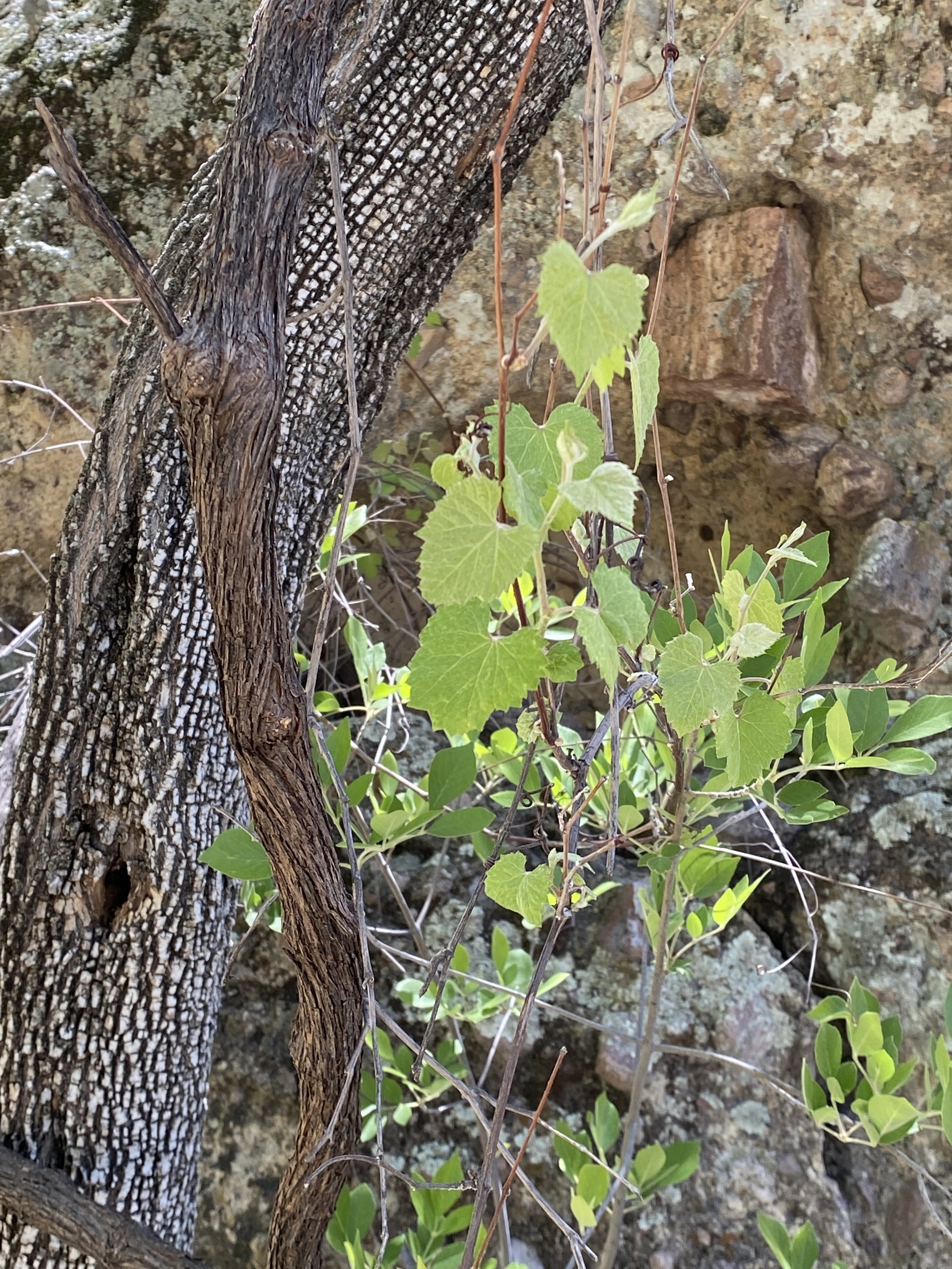

The snare tree 12 years after Macho B’s death.

I sketched the tree, which has three very distinct claw marks and the diagonal slash of the snare wire. He fought and fought and fought the snare, ruining his foot, breaking a tooth.

It was very emotional to sit there knowing what happened. The entire story is told in Janay Brun’s excellent book Cloak and Jaguar: Following a Cat from Desert to Courtroom.” Janay, one of the contractors working for the researchers who set up the study, became a vocal whistle-blower about the ethics and illegality of the project. She was even prosecuted for being accessory to illegally taking an endangered species. None of the state and federal agency staff ultimately responsible for the project were charged or reprimanded. (You can also read much more detail on Janay’s blog: https://whistlingforthejaguar.wordpress.com)

I collected red and yellow iron-oxide (ochre) rocks from under the tree, and orange ochre rocks from upstream, from which to make paint to complete a formal painting for Chroma Sonorensis. My field sketch study-concept sits at the top of this article.

I'm calling the pigments "Onça Ochres" — orange for Macho B's pelt, red for his blood that coated the tree and soil where he tore his paw and fought for his life, and yellow for the canyon walls that look over his spirit.

“Onça” is Brazilian-Portuguese for jaguar, and the scientific name for jaguar is Panthera onza, North America’s only roaring cat.

Yesterday I completed initial processing of these wild pigments, crushing the rocks, grinding them, and sifting to 200 microns so I can mull them into paints with gum arabic. Curious about the volume of rocks I collected, I weighed them: 2.7 kilograms! No wonder I was tired after our long hike out—but the results were worth it. I love the three colors, they will make a perfect Macho B portrait.

Below is a gallery of images from the canyon, including of the small shrine where Macho B is remembered. I left a small piece of red ochre.