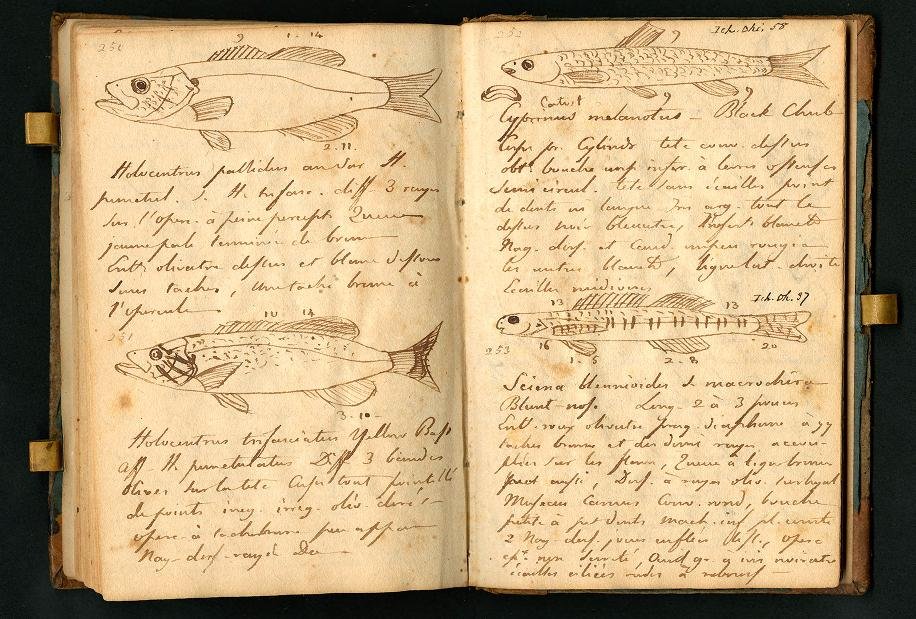

Field notes in the Americas by Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, ca. 1820s.

Explorers have been keeping hand-written field notes—with or without sketches—for hundreds of years, if not many millennia (on observing many rock art sites, I’ve been struck by the possibility that early humans were using rock and pigment to record their travels and nature information for hunting and gathering, and sharing their findings with others . . . such as at the large complex at the Neolithic Tweifelfontein in Namibia, which includes a large slab map showing water holes and game; see my field notes from this site at the bottom of this post).

A spread from my book Master of Field Arts showcasing the journals of Charles Darwin, Meriwether Lewis, and Thomas Orde-Lees—as well as a page from my humble journal during a weeklong biological survey of the Sierra los Locos, Sonora, Mexico in 2019. [Click to enlarge.]

Browsing the field notes of science explorers such as Charles Darwin (1809–1882), Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), Edgar Mearns (1856-1916), and Constantine Samuel Rafinesque (1783-1840) gives us an incalculable wealth of knowledge of the lands they explored and the human cultures and nature they observed. Darwin’s branching tree of evolution (right) with the scribble “I think . . .” never fails to give me the chills.

From the journals of geographer-explorers such as Thomas Orde-Lees, a member of Shackelton’s Endurance crew on the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition in 1916, and Meriwether Lewis (1774-1805) and William Clark (1770-1838) from their Corps of Discovery, we discover new lands and learn first-hand the astonishing courage and skill needed to push the limits of human exploration.

Their meticulously detailed and illustrated field journals are priceless to humanity, as I mentioned, for their wealth of data, but also as roadmaps of human learning through exploration. Our boundless curiosity coupled with our ability to record what we see is one of the critical attributes that sets apart humans from other species.

Alexander von Humboldt’s journals from his Americas explorations ca. 1799–1800. (from https://humboldt.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/work/?lang=en)

List of bird species observed by Edgar Mearns (1856-1916) at Fort Verde, Arizona, in 1884.

The Importance of Field Notes Today

Field notes are still critical tools for field scientists and explorers, and yet the practice is waning with the advent of computers and pocket devices with 12-mexapixel cameras. You could say that I have been on a mission for the last several years to not only help save the tradition of venerable classic field notes but to also spread the love of recording nature to everyone—from kids to grandparents. John Muir Laws (The Laws Guide to Nature Drawing and Journaling) says it best: “Keeping a journal of your observations, questions, and reflections will enrich your experiences and develop gratitude, reverence, and the skills of a naturalist.”

In these digitally cacophonous times that are robbing us of the ability to focus intently on one thing for very long, connecting with nature through careful observation and note-taking is more important today than ever in the past. Keeping a field journal may be the key to healing our digitally fractured minds.

I’ve been keeping field journals for almost 50 years, since I was eight years old and my Dad built me a Stevenson screen stocked with an array of weather instruments—every day at 4 pm I would head out with my notebook to record the daily weather and make notes and field observations. That—along with rockhounding expeditions with Dad and wildflower safaris with my Mom—cemented my lifelong love of nature observation, scientific discovery, and exploration (not to mention I’m still a weather nerd).

Grinnell’s narrative journal page from a 1910 field expedition to Pilot Knob. I followed his method starting in college—and still do, albeit with more drawings and color. I keep a small field notebook for jotting quick notes when I’m traveling or moving quickly, in addition to my larger narrative journal (see below).

When I started studying ecology and evolutionary biology in college, my field notes became serious records of natural history data using the Grinnell Method of scientific note-taking (a thorough documentation style, which included four components: a field notebook, a field journal, a species account, and a catalog of specimens; see right).

“Our field-records will be perhaps the most valuable of all our results. …any and all (as many as you have time to record) items are liable to be just what will provide the information wanted. You can’t tell in advance which observations will prove valuable. Do record them all!”

– Joseph Grinnell, 1908

About eight years ago I started adding sketches and watercolor to my field notes, adopting a more “journaling” style and yet still always including the critical metadata and nature data.

Sketches and data from my journals have been used in several books written by me and my husband, Jonathan Hanson. In 2020 I published Nature Journaling for a Wild Life, to encourage anyone who wants to begin keeping a field or “nature” journal, and in 2022 Master of Field Arts, a sort of “master’s degree” for the next level to becoming a lifelong naturalist and explorer.

Obviously we can’t all be Charles Darwins or Alexander von Humboldts, but we can explore the world around us and make observations and fall in love with the process of discovery.

Time and again I return to one of my favorite published journals of discovery, the superbly readable The Sea of Cortez: A Leisurely Journal of Travel and Research by longtime friends John Steinbeck and Ed Ricketts. Published in 1941, it is the full and shared vision of their scientific collecting expedition aboard the Western Flyer sailing out of Monterey. The book is part travel journal, part philosophical essay, as well as a nature journal and a catalogue of species Grinnell would highly approve of. Steinbeck described the purpose of the journey was

“to stir curiosity”

. . . but my favorite line from the book perfectly captures the larger context of exploration and observation (and recording those observations in our journals):

“It is advisable to look from the tide pool to the stars, and then back to the tide pool again.”

* * * * * * * * * * *

Field notes page from our crossing of Botswana in 2019.

Above and below: Studying and documenting a large (and probably 1,000+ year-old) Welwitschia mirabilis in the Ugab River region of Namibia, 2019.

I love that my field journal—made for me by my husband over 25 years ago (and my companion on tens of thousands of miles of exploration and field work on five continents) so closely resembles the journal of Meriwether Lewis (right).

Resources for exploring historical and modern field notes:

Start with the Smithsonian Institution’s Field Book Project (scroll to the bottom of the page to access the archives links) at https://siarchives.si.edu/about/field-book-project

The goal of the Field Book Project is to promote awareness of and access to thousands of scientific field notes in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution Archives, and holdings at the National Museum of Natural History and the Smithsonian Libraries. It began in 2010 as an effort to bring to light these hidden collections with a goal to catalog 5,000 field books and provide online access to those records, a goal graciously funded by the Center for Libraries and Information Resources (CLIR). At this point, the Project has cataloged over 9,500 field books and digitized over 4,000.

Another rabbit hole to explore is the UC Berkeley Museum of Vertebrate Zoology’s Archives Field Notes collection: https://mvz.berkeley.edu/mvzarchives/

* * * * * * * * * * *

This post is an update to my 2019 post, “The art of seeing instead of looking: reasons to keep a nature journal”.