Google Earth captures the range of colors of northern Arizona’s Painted Desert.

The idea took hold on our first trip into the red desert center of Australia. Surrounded by vast and glowing rusty-red sand seas awash in bright yellow flowers and sea-green eucalypts, I began to think about painting that iconic landscape with watercolors made from the place itself. I collected red sand from several places, sealed it in jars, and—because I hold a Trusted Traveler fast-lane pass from U.S. Border Protection and they most definitely frown upon carrying soil samples in one’s luggage (violate one rule and you lose your pass forever)—I posted them home (*see notes at end). A year later, surrounded by vast and glowing peach sand seas flanked by jagged black slashes of mountains in northern Mexico’s Gran Desierto de Altar, I was again inspired by the rich colors and dramatic landscapes—and this time I had some tools with me to do a little experimenting with the local magnetite to create paint (which I wrote up in this post HERE).

And so Feral Watercolor was born: to collect local pigments and ink-making materials with which to create place-based art.

With jars of material from several continents—including three gorgeous colors from northern Arizona’s Painted Desert—I invested in a small, high-quality hand-crank ore-crusher called The Crunch: 1/4-inch steel, cam-driven, and made in the U.S. (sold on eBay by “GoldMLode”).

The Crunch will process rocks as hard as quartz (it’s made for people who look for remnant gold in mine tailings) into powder fine enough to sieve down to 70 microns—small enough to make make traditional-style earth pigments for making watercolor (reference: Bruce MacEvoy’s exhaustive website Handprint; on particle size of pigments for making watercolor, modern and historical).

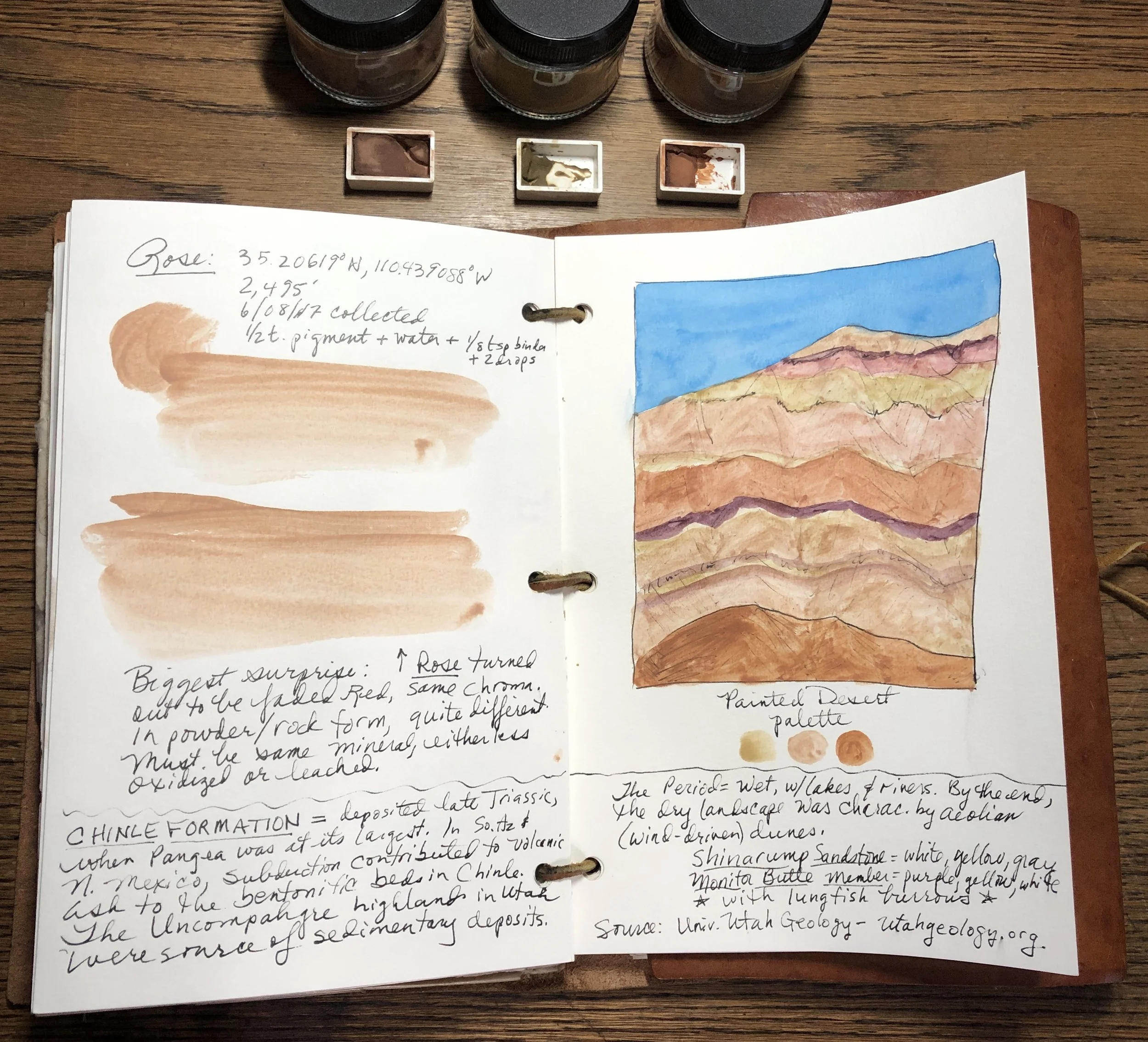

First through The Crunch were the yellow ochre-like rocks, part of the Chinle Formation that was laid down in the late Triassic (200 million years ago) as the seas around Pangaea retreated and alluvial plains were covered in silt, mud, and sand—with plenty of iron, manganese, and aluminum. Oxidation (either aerobic or anaerobic) created the reds, purples, yellows, greens, or grays. Would these gorgeously colored rocks result in similar paint hues?

After running through The Crunch a couple times, I put the sand-sized grains through four high-quality stainless steel sieves (made by Talisman in New Zealand; available on Amazon), starting with 40-mesh, then through 60, 100, and finally 200, which yields about 70-micron particle size.

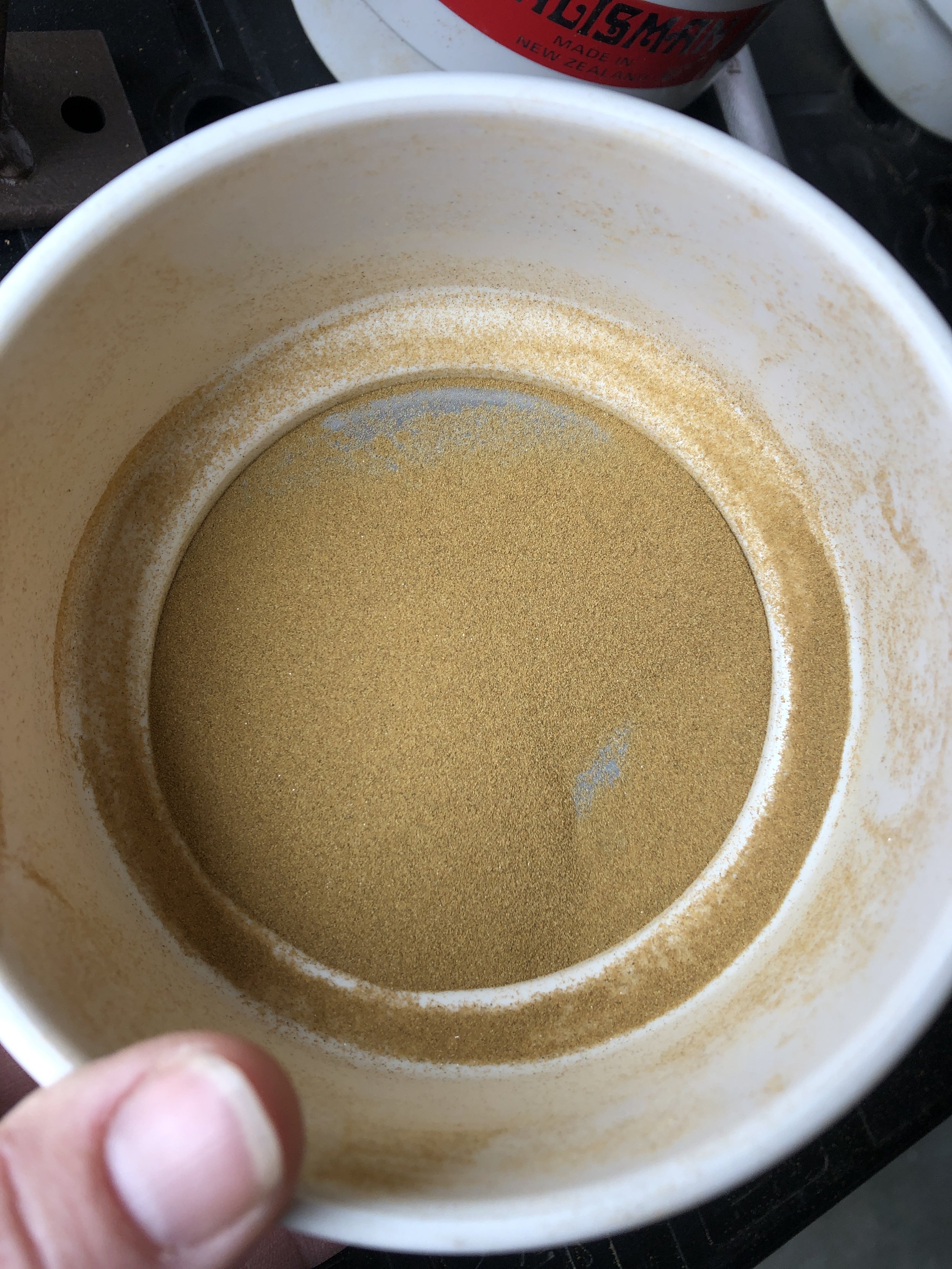

In the 100-mesh sieve . . .

. . . final yield of 200-mesh . . .

. . . very fine and still bright.

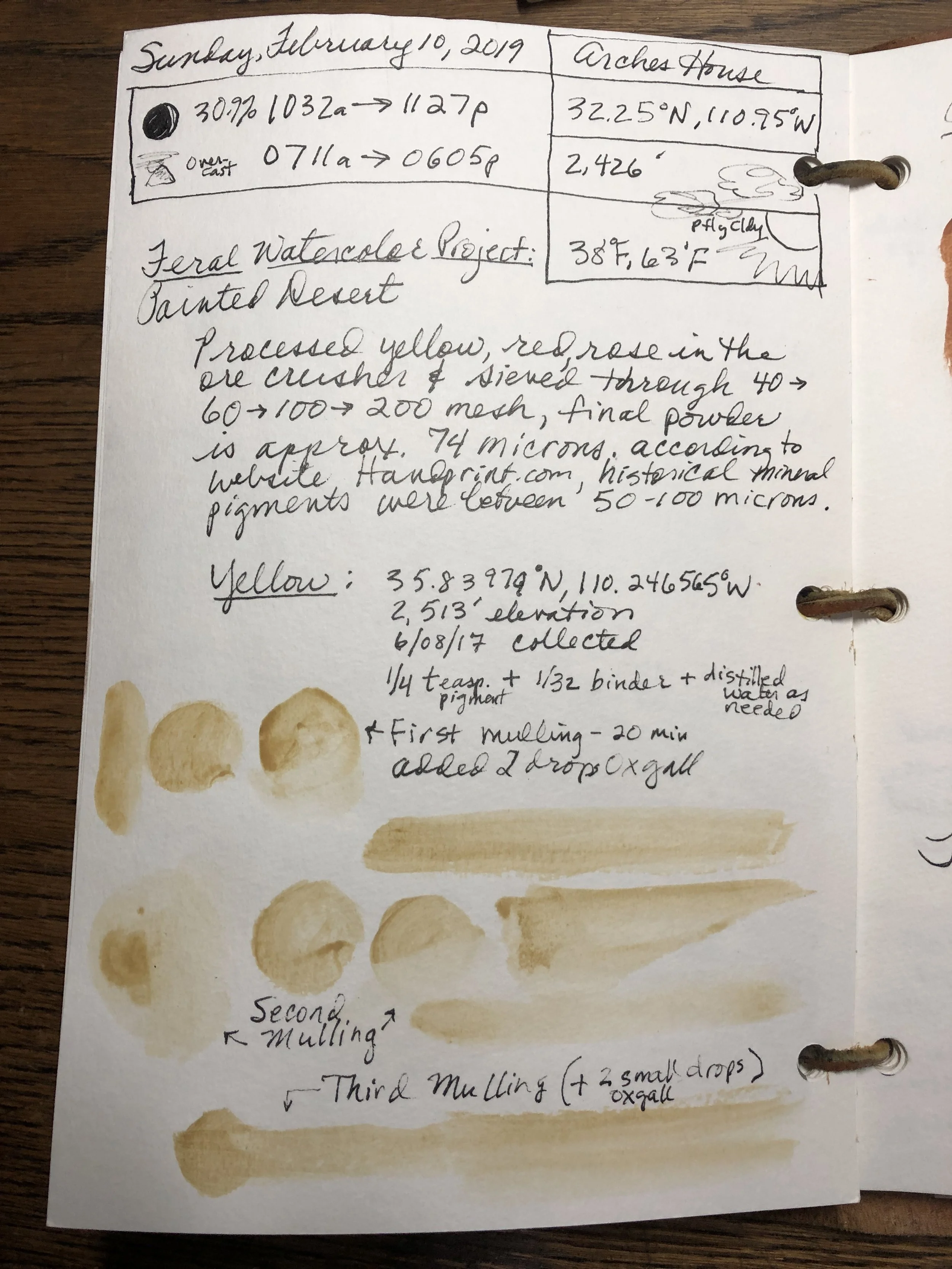

Now at the mulling bench . . . I processed the 70-micron yellow pigment with gum arabic, Sonoran Desert honey, and oxgall to create watercolor paint (see my notes below, along with swatches of color from three stages of mulling, which takes about 30 minutes per stage.

On paper the yellow was not as bright as in pigment, but it has a lovely warm hue, and nice coverage. Almost between a yellow ochre and umbre.

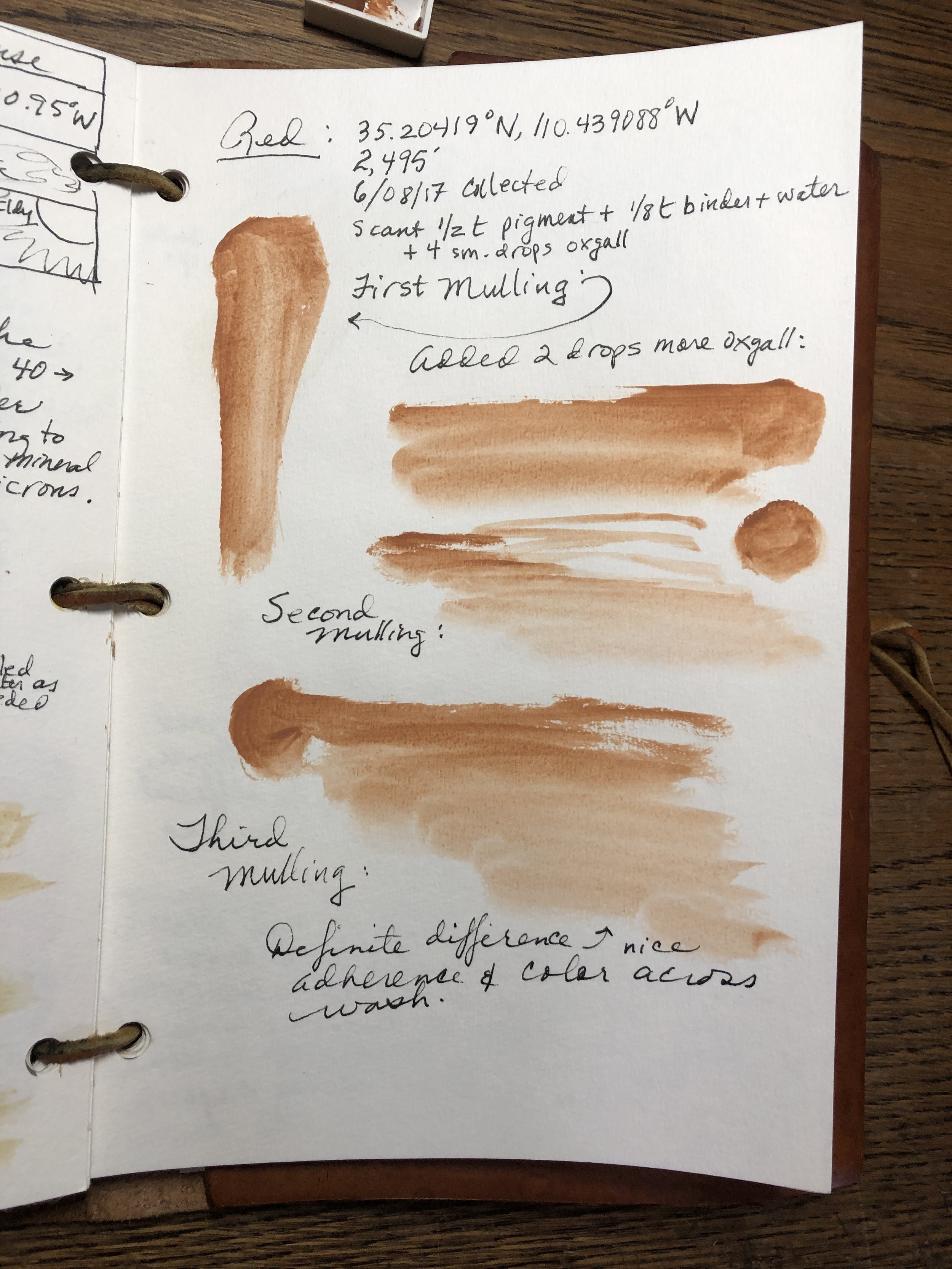

Next up was the very dark red ochre-like pigment. Its hue on the mulling glass was eye-popping!

And on paper it did not disappoint:

Finally, I processed the rose—which had a lovely “ashes of rose” color in pigment form. Upon processing into paint, its hue on paper was more faded-red, though it’s growing on me!

In all a very satisfying first step in the Feral Watercolor project. I noted that I should have added slightly more binder to the paint, as it is drying too fast and cracking in the pan and the flow is not what I’d like. I have several other regions’ pigments to process and test, and then it will be time to create paintings.

*NOTES:

Where to collect: I collect from roadsides or private land where I have permission. There are also state and local parks dedicated to "rockhounding" where it is legal to collect. Do not collect in any local, state, or national park. National forests and BLM may be a bit more open to collecting (since many allow firewood collecting), so you can contact your local office to find out

Travel and collecting: If when you travel you would like to collect raw pigments (rocks or soil) for processing, follow the same guidelines as above, and you should be aware of not only border restrictions for bringing soil back to your home country, but also environmental smarts: soil contains seeds and microbes, and if you are transporting them home, that can be detrimental to your home environment. I make sure I run my pigments through the microwave to semi-sterilize, and then always keep it in sealed containers and never, ever dispose of any of it outdoors or down the drain. I treat it like a toxic chemical.

Safety: always wear eye protection and a dust mask when handling and processing rocks and pigment into paint. Natural pigments are not “safe” because they are “natural”—remember that they contain metals such as manganese and aluminum (among many others) and you are grinding them into powder that easily goes airborne and is inhaled.