Et tu, Filson?

Lumberjacks well-equipped in early C.C. Filson clothingThe history of exploration in the 20th century is littered with outfitters that got their start and earned fame by offering high-quality, durable clothing and equipment suitable for demanding use in the field, and which then devolved into mere fashion outlets flogging branded urban wear showing little if anything in common with their heritage.

Lumberjacks well-equipped in early C.C. Filson clothingThe history of exploration in the 20th century is littered with outfitters that got their start and earned fame by offering high-quality, durable clothing and equipment suitable for demanding use in the field, and which then devolved into mere fashion outlets flogging branded urban wear showing little if anything in common with their heritage.

Walk into an Abercrombie and Fitch store today and tell a clerk you’d like to be fitted for a new 16-bore sidelock shotgun. You’ll probably find yourself chatting with a policeman in short order. Yet for seven decades A&F was the premier U.S. outfitter for outdoorspeople, whether they were headed out for a weekend of flyfishing or, as one customer and former U.S. President was in 1909, off to Africa for a year of shooting and collecting for the Smithsonian. One could figuratively walk into an A&F store in one’s underwear and leave ready to tackle the Dark Continent. But in 1976 the company declared bankruptcy, and the hallowed name was bought by Oshman’s, which relaunched it as a mail-order shadow of its former self. That was a mild fate compared to the eventual acquisition by The Limited, which has morphed Teddy Roosevelt’s outfitter into . . . well, something he would not recognize.

Abercrombie and Fitch, then . . .

Abercrombie and Fitch, then . . . . . . and now.

. . . and now.

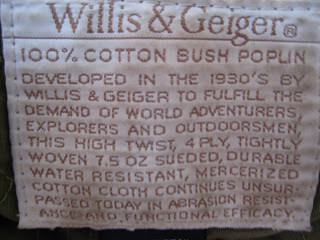

There was Willis and Geiger, founded in 1903, who supplied Roald Amundsen, Amelia Earhart, and the Flying Tigers, among many others. When Charles Lindbergh needed a shearling suit for his flight over Antarctica, he turned to W&G, and when Ernest Hemingway wanted a bush jacket made to his own design, he did likewise. I still have several carefully hoarded W&G shirts and bush jackets in their bespoke, tough Bush Poplin.

In a twist of fate, W&G was Abercrombie and Fitch’s largest creditor when it filed Chapter 11 (because of branded merchandise), and it did not survive the writeoff. A new owner, Richard Avedon, revived the brand, the products, and the quality, but the writing was on the wall. Various takeovers ensued, production of new items moved offshore until the company was purchased by Lands’ End, which let it fade away ignominiously. (Speaking of which, does anyone here recall that Lands’ End got its start selling foul-weather gear to offshore sailors?)

There are others. Eddie Bauer was a sportsman who patented the quilted down jacket, supplied the military in WWII, and outfitted Jim Whittaker on the first U.S. ascent of Mt. Everest. Once the company was sold in 1968, new corporate owners General Mills turned its focus to everyday clothing and began capitalizing on the evocative name, a marketing assault that hit its nadir when several Ford 4X4 vehicles—and eventually a minivan—received outdoorsy cosmetic packages and were sold as the “Eddie Bauer Edition.” And although Banana Republic’s history dates from just 1978, the company quickly gained a reputation for fine and practical outdoor clothing, only to lose it just as quickly after selling out to Gap Inc.

Jim Whittaker atop Mt. Everest, in an Eddie Bauer parka.

Jim Whittaker atop Mt. Everest, in an Eddie Bauer parka.

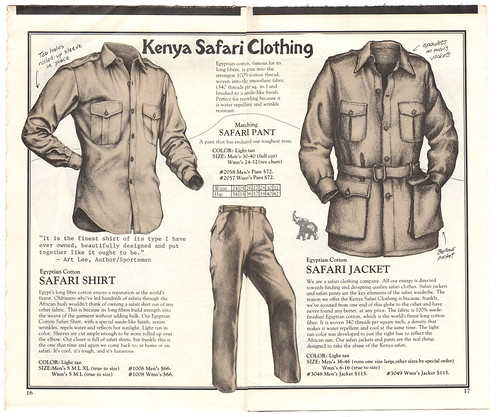

A page from a Banana Republic catalog.

A page from a Banana Republic catalog.

One company weathered all this with standards intact. Clinton C. Filson was born in 1850, homesteaded in Nebraska, then opened a loggers’ outfitting store in Seattle in 1890. In 1897 his business expanded to outfit prospectors on their way to the Alaska gold rush with sleeping bags, boots, and clothing. With the end of the rush, it was natural to shift emphasis to equipping sportsmen with gear for hunting and fishing trips. The family ran the company and the catalog remained small for the next seven decades, until a skiwear manufacturer named Stan Kohls bought the name and expanded the line hugely, while retaining the original design philosophy and maintaining exceptional quality.

This period was arguably the golden age of C.C. Filson. The company produced clothing ranging from heavy-duty outerwear for winter duck hunting to Feathercloth shirts suitable for the hottest African savannah, and luggage seemingly immune to wear. Through the 90s and into the 2000s, Filson shirts became nearly a uniform for me. One medium Filson duffel has made, as near as Roseann and I can figure, 13 trips to Africa between us.

One of our Filson duffels on its . . . 10th? . . . trip to Africa.Sometime around 2005, I noticed some production had shifted offshore. Although the quality remained, to be honest, apparently the equal of the U.S.-made predecessors, prices not only did not drop but began rising to heights at which tearing the sleeve of a Feathercloth shirt on an acacia really hurt. If I’d looked, I would have discovered that at this time Filson had been purchased by a California-based private-equity firm and a former Ralph Lauren executive.

One of our Filson duffels on its . . . 10th? . . . trip to Africa.Sometime around 2005, I noticed some production had shifted offshore. Although the quality remained, to be honest, apparently the equal of the U.S.-made predecessors, prices not only did not drop but began rising to heights at which tearing the sleeve of a Feathercloth shirt on an acacia really hurt. If I’d looked, I would have discovered that at this time Filson had been purchased by a California-based private-equity firm and a former Ralph Lauren executive.

Uh oh.

Still, I remained loyal because the products seemed to stay consistent, they lasted long enough to make the investment worth it, and there was really nothing else I found that I considered equivalent.

Then, a couple of months ago, in preparation for a trip to Kenya, I went to the Filson website to buy a couple of new Feathercloth shirts, steeling myself for the $70-per-shirt hit on my bank account. I found, to my chagrin, that the feathercloth shirt had been discontinued.

No, it was worse—it hadn’t been discontinued, it had been rebranded. It’s now called the “Seattle Shirt”—and the price has doubled magically to $140. Each. So much for a shirt to wear in the bush—clearly this one is no longer intended to risk danger worse than having a latte spilled on it.

Expedition to Starbucks, anyone?

Expedition to Starbucks, anyone?

A little research reveals a disturbing development: “Filson Holdings” was sold in 2012 to Dallas-based Bedrock Manufacturing, which is backed by the founder of the fashionable accessory manufacturer Fossil. Note that “fashionable accessory” part. As if to confirm my worst fears, it was just this time I happened to catch the news of the “Filson Edition” AEV Brute, a $130,000 customized Jeep pickup outfitted with twill and leather seats (Filson logo prominently displayed), brass trim, and a rear-seat organizer equipped with special Filson bags.

Sigh . . .

It’s actually too early to write off Filson altogether. For example, the company has moved production of many products back to the U.S., a commendable effort. However, the prices of those, and other, items have ballooned so comically that it’s difficult to avoid the conclusion the company is targeting an entirely new customer base—one with whom a name such as “Seattle Shirt” will resonate.

I know I’ll be looking elsewhere for my Kenya shirts.

When I first found the $140 “Seattle Shirt” on the Filson site, I sent an email to the generic Filson customer service email expressing my disappointment, and describing my history with the company’s products in field use ranging from the Arctic to the Sahara. To my surprise, I received an extensive personal reply from a customer service manager named Phil, who assured me that others had written expressing similar opinions, and that all had been forwarded to management.

I later forwarded the original OT&T post above to Phil, along with the comments, as an FYI. Very quickly I received this back from him:

Jonathan,

Thank you for sharing your post and the comments. I read them all and will happily forward this up the food chain to as many people who will read it as I can find. Just a couple comments.

If you will forward the boot guy to me I will take care of him.

You are not the first to mention pricing. Others have and it is an issue management is aware of. As for the AEV Jeep—it is a marvelous machine (we have one here in Seattle) that nobody ever expected to sell many of. I went to see the AEV website and their videos of a similar jeep climbing mountains and such. Very impressive.

I can not answer for everything but I can tell you that many costs, for example that of our Moleskin shirt fabric, have more than doubled recently. Cotton and wool prices have gone way up, as has the price for leather.

Bedrock has been very good for Filson. They have the money to invest in us, which has allowed us to make critical infrastructure and software updates that otherwise would not have been possible. Things such as this allow us to bring more manufacturing back to the USA.

Filson lives for our customers' comments and on their opinions. If we fail to listen to them, we fade away. I will be happy to answer any questions you have as best I can, and please direct your friends to email me here and I will do my best for them.

Thank you,

Phil L

I’ve forgotten how many other companies I’ve written to, with either praise or critique, and received nothing but a toneless boilerplate response, so this is indeed heartening. And Tim (the “boot guy”) will shortly be receiving a new pair of boots. (Phil told him they’d had trouble with the initial supplier of the boots and had switched to a different source.)

It would have been easy for Phil to completely ignore my email, yet he’s not only engaged me several times but has forwarded this thread to others at Filson. So I believe him when he says the company is determined to be responsive to their core customers. But will they need to redefine who that core is?

Consider this wonderful note from the comments section:

Jonathan,

My Dad purchased a Filson upland coat in 1945 upon his return from the war in Europe. It was handed down to me and I've handed it off to my eldest son, grouse blood and all. He still wears it. It's going on 70 and I just turn 70.

Bill

A revealing story regarding Filson quality. But let’s examine it more closely. It should be obvious that Filson can no longer expect to remain profitable by selling upland coats only to grouse hunters such as Bill’s father (or elk hunters such as myself). Hunting is (sadly) in decline in the U.S., although fishing seems to be holding on somewhat better. Much other outdoor activity seems irretrievably wedded to modern technical fabrics (although my Barbour has outlasted several Gore-Tex alternatives). Nevertheless there are many outdoor pursuits besides field sports for which Filson makes superbly suitable clothing—and of course there is their equally superb luggage. I wonder, then, if Filson can defy history and remain true to its heritage, while profiting as much as is necessary from sales to those after nothing but the look. (Random related example: Redwing boots—the orangey-colored moc-toe, eight-inch-tall, white-ripple-sole model beloved of truck drivers, bird hunters, and construction workers—are apparently now the footwear of choice among hip-hop artists. Go figure.)

We’ll stay tuned . . .