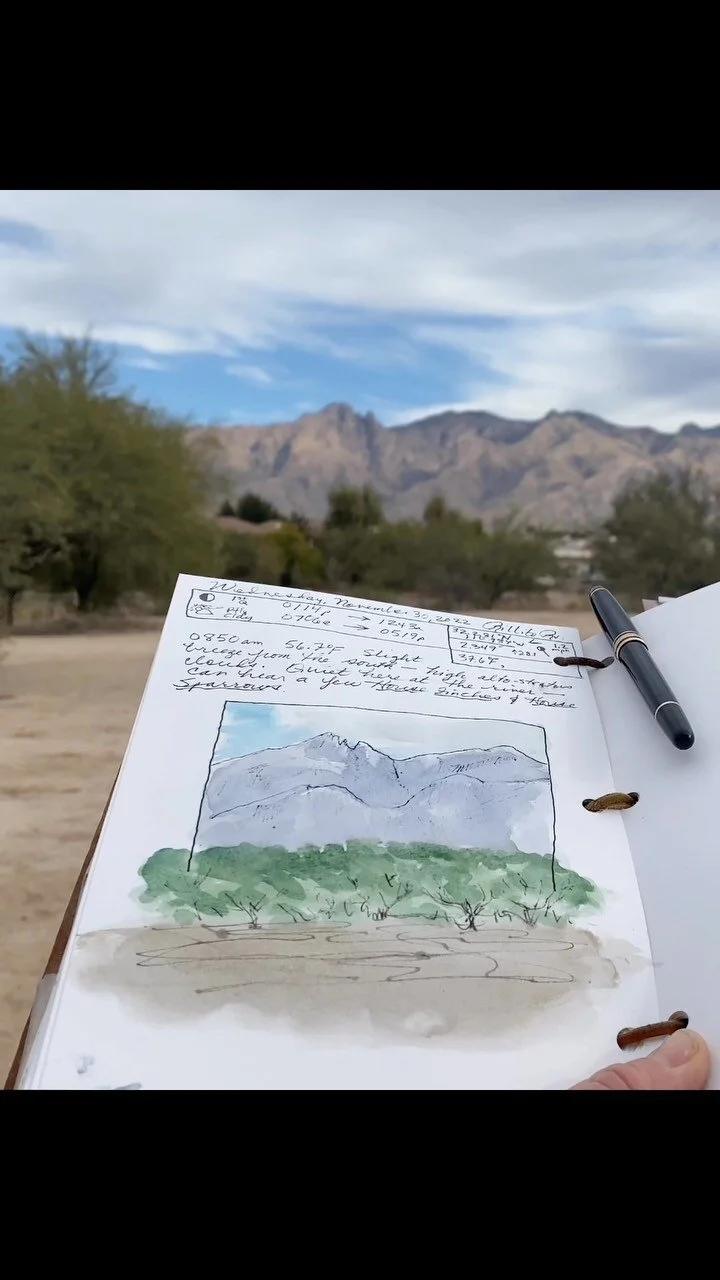

Roseann hosts the Constant Apprentice blog as a place for curious humans to explore craft, visual arts, writing, nature, food, and all things classic, then and now. For Jonathan’s blog, select the Overland Tech & Travel tab.

Clear Perspex Palette with Magnet Strip

from $13.00

Master of Field Arts

from $35.00

from $36.00

Sign up for periodic updates—free tutorials, new books, essays, and more! We don’t over-do it, promise.

ROSEANN HANSON hosts the Constant Apprentice field arts and science blog as a place for curious humans to share exploration & enquiry through science, nature, writing, visual arts, and classic crafts, historical and present. [About Roseann]

{Science} {Visual Arts} {Writing } { Craft } { Travel } {Nature} {Classes}

Posts by Interest

- Bootcamp 6

- Field Arts 26

- New Mexico 3

- Travel 51

- Books 6

- #naturejournaling 1

- Art and Science 2

- Idaho 1

- Montana 1

- Master of Field Arts 1

- Desert Laboratory 1

- Tumamoc 2

- Metadata Mnemonic 1

- Natural Pigment 11

- Mars 1

- SoAzNatureClub 1

- Index 1

- Gift 2

- Overlanding 12

- Class 6

- Feral Watercolor 1

- COVID 1

- Journal 20

- Nature 71

- November 2019 1

- Sonoran Desert 1

- Creative Process 9

- Africa 24

- Kenya 7

- Land Rover 2

- Culture 3

- Grand Canyon 3

- Overland Expo 2

- Ravenrock 59

- Conservation 12

- Mexico 9

- Food 12

- Asia 1

- Plants 2

- Tucson 1

- Brooks 2

- Raleigh 4

- Recycled Art 2

- Porsche 2

- Tanzania 11

- El Aribabi Conservation Ranch 5

- U.S. 13

- Motorcycle 1

- I {heart} . . . 3

- Found Object Art 1

![Around the World in 80 Rocks, Fossils, and Formations - No. 5, Africa (pt. 2) [FREE workshop]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5395fbd3e4b003747ed3b60a/535876a1-f577-471c-9cab-77c9ed186832/Egypt57.jpeg)