The original Micro-Start XP-1, the first lithium-powered compact jump-starting system on the market, gained instant legend status at the Overland Expo when Tim Scully and I daisy-chained three of them and welded two quarter-inch slabs of steel together, both impressing and horrifying Scott Schafer, the company’s founder. While emphatically not an endorsed application (and probably a deal-killer for any warranty claim), it demonstrated the resilience of the product.

Those same three units went on to do yeoman service at the Expo and on a dozen group trips, jump-starting I have no idea how many SUVs, trucks, and motorcycles, in addition to running our portable devices at the show and other events. We’ve never been without one in each of our vehicles since, and when the heavy-duty XP10 was introduced I put that one in our 6.0-liter diesel Ford F350.

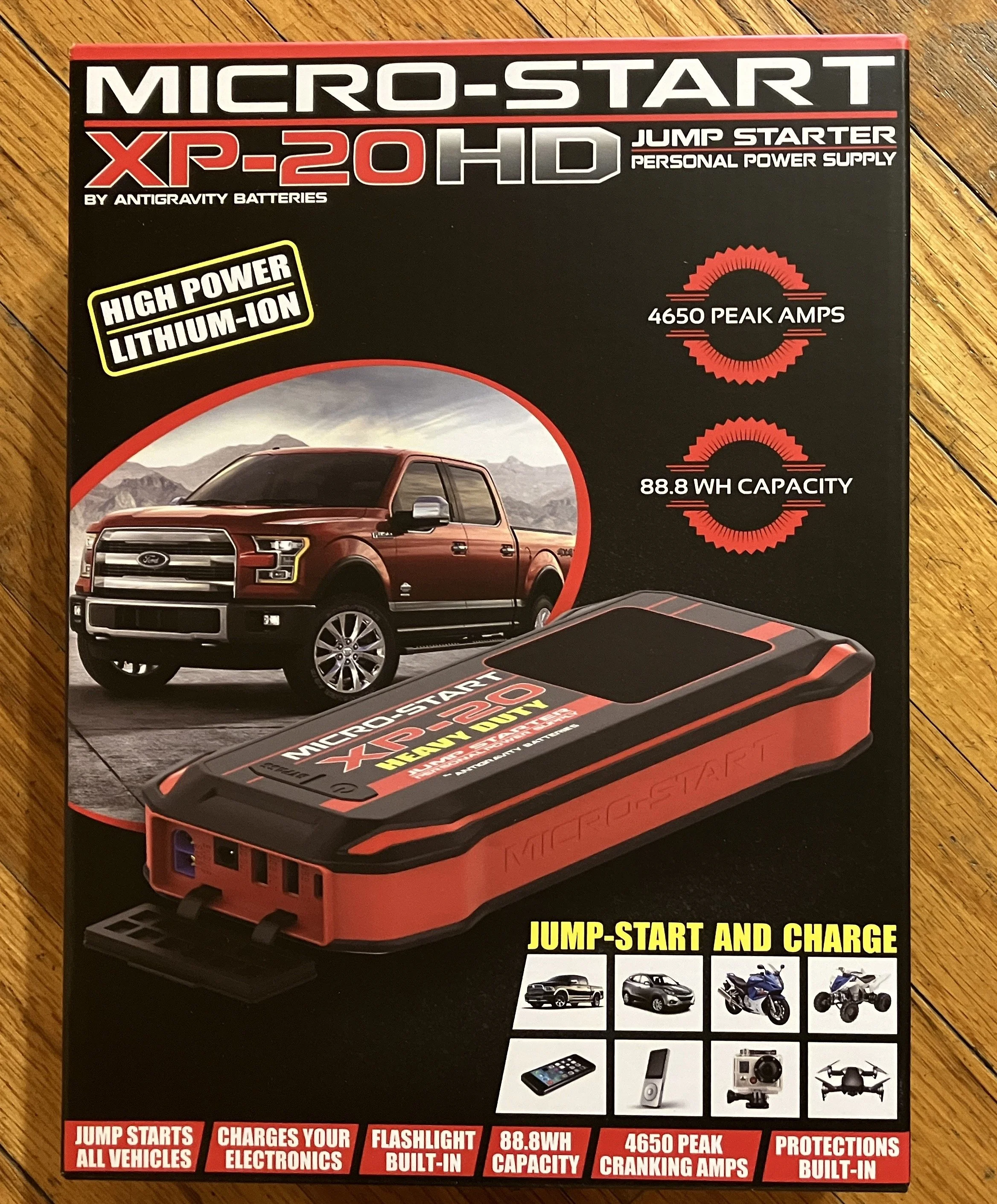

Recently, at long last, two of our original XP-1s began to swell slightly, a sign of impending failure even though both still functioned. So I went to the Antigravity website to see what was new—and found quite a lot. There’s now an economical—and super-compact at three by six inches—XP-3 model, just $120, nevertheless suitable for gasoline engines up to 5.7 liters. The XP-10HD exceeds the capabilities of our already stout XP-10. But what caught my eye were the XP-20 and XP-20HD, the new top-of-the line models with seriously enhanced specifications. So I had the company send me an XP-20HD ($249).

And impressive specs they are. For comparison, the XP-10, which as I mentioned is suitable for starting big diesel engines, offers 300 amps of starting current with a 600-amp peak and a total capacity of 18,000 mAh (milliamp hours). The XP-20HD puts out a massive 930 amps of starting current with a 4,650-amp peak, and total capacity is 24,000 mAh.

That’s not all. Both XP-20 models employ USB-C PD 100-watt charging capability, and will fully recharge in one hour from either a 12VDC or 120VAC source. Each also incorporates a large LED screen that reads out percentage of charge and the power draw of whatever device is connected to it (or the input wattage when charging). When I first used the XP-20HD, to power an iPad at a book festival for taking credit-card payments, the output reading alerted us to the fact that the iPad was running a background program that was drawing excess power. Nice. The XP-20 models will also power/recharge laptop computers via the USB-C output/input port.

Large LED screen shows percentage of charge, and input (or output) wattage.

Oh—incidentally—the XP-20HD will start diesel engines of up to 8 liters and gasoline engines of up to 10 liters. That should take care of most of the overlanding vehicles I know . . .

In the years since the XP-1 first came out the concept of compact jump-start systems has exploded in popularity, and you can now find a dozen or more brands you’ve never heard of on Amazon at discount prices. Personally, my experience with the Antigravity units is enough to retain my loyalty, but I thought I would do a comparison, and so took a look at a friend’s Amazon-sourced unit from GOOLOO, the GP400, which sells for a very tempting $130. (I studiously subsumed my editorial annoyance at the ALL-CAPS brand name and did not let that sway my opinion.)

The GP400’s starting specifications are impressive, if about 15 percent below those of the XP-20HD: 800-amp starting current and 4000-amp peak compared to 930 and 4,650 amps. Much more notable is recharge time: five hours for the GOOLOO versus one for the Micro-Start, thanks to its USB-C PD connection and 100-watt capability. That same capability also allows a topped-up XP-20HD to completely recharge a dead MacBook Pro in about an hour—the GOOLOO could theoretically charge the same MacBook, but at a much slower rate. (With a USB-C cord you can even use the MacBook’s Powerbrick to recharge the Micro-Start from a 120/240V source. Got that?)

Other bits: The battery clamps on the GOOLOO are described as “all-metal,” while the clamps on the Micro-Start are solid copper. And the GOOLOO lacks the extremely useful digital readout of remaining capacity and power draw. I actually liked the GOOLOO’s semi-hard case better than the Micro-Start’s semi-floppy case, and the GP400 does offer a lot for the money; however, taken altogether I think the XP-20HD more than justifies its price premium, especially considering Antigravity’s stature and reputation.

Even if, like many of us, you have a dual-battery system in your vehicle, a Micro-Start offers additional peace of mind against the possibility of a no-start situation—not to mention numerous opportunites to be a hero helping out others. The advanced device-powering and fast recharging capabilities of the XP-20 and XP-20HD models catapult them even further beyond the original brilliant Micro-Start concept. Impressive.

That reminds me . . . I’ve got a bit of welding I need to do on the FJ40’s rear rack.

Kidding, Scott. Kidding.