Overland Tech and Travel

Advice from the world's

most experienced overlanders

tests, reviews, opinion, and more

Continental Divide vehicle report

What sort of mischief can 1,600 uninterrupted miles of mixed corrugations, rocks, potholes, mud, and even some pavement wreak on a diverse group of four-wheel-drive vehicles? We found out on the recent Continental Divide trip organized by Rawhyde Adventures and us.

Our lineup on the ten-day journey included two Toyota Tacomas (one mounted with a Four Wheel Camper), two Ford Raptor pickups (one also mounted with a FWC), two Sportsmobiles (nine years apart in age), two Toyota FJ Cruisers (one towing an Adventure Trailer), two four-door Jeep Wranglers, one nicely maintained 1990 Ford Bronco, one newly restored and modified FJ60 Land Cruiser, a four-wheel drive Chevy Van conversion, and, occasionally, a Ford F250 pickup belonging to the Rawhyde staff’s self-taught 21-year-old mechanic/welder/marshmallow toaster (more on that later), Phil. Sadly, a Land Rover Defender 90 powered by a 200TDi diesel failed to make the start, after a blown head gasket and several other issues finally sidelined it despite valiant attempts by its owners to rectify things and meet us partway along the route.

We knew we were pushing the weather envelope on the trip, as it was scheduled right after the Overland Expo WEST, in late May. Additionally, the Rockies had experienced heavy snow fall just prior to our journey, so it was clear in advance some of the high passes would be . . . impassible. However, our group seemed to take this in stride as a more enjoyable challenge than cruising over the same passes might have been later in the year. One attempt, at a high pass above Lake de Nolda and the Alamosa River, involved first pulling a large fallen tree off the trail, then blasting through several drifts until the lead Ford Raptor found itself high-centered, all four wheels rotating uselessly, in a snow bank too deep to shoulder aside. In this case, everyone agreed that trying and failing was more fun than easy success.

Mostly, though, the miles we drove comprised easy to moderate backcountry routes with miles and miles of hammering from corrugations (or washboard if you prefer), and low-speed bouncing over freeze-induced potholes. The effects became apparent early on.

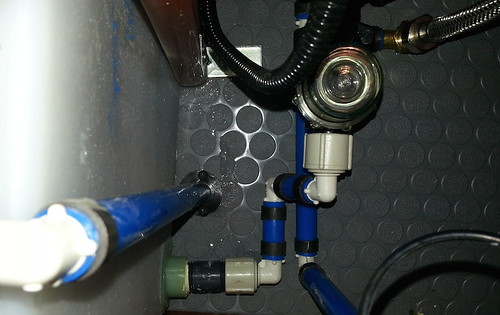

Both Sportsmobile owners glanced back into their living areas during a day’s trek to find their carpets soaked. The rough roads had caused (yet-to-be-determined) leaks in the vehicles’ plumbing systems, resulting in complete loss of water in the main tanks. Despite this, everyone was impressed with the Sportsmobiles’ utility and capability, especially considering their imposing size and 10,000-pound-plus GVW.

The FJ60 had just been the subject of a near-complete rebuild, including the installation of a factory 1HZ six-cylinder diesel engine with a turbo kit, plus a five-speed transmission, along with an extensive array of cargo-containment slides and suspension modifications. In fact, its owner, Adolfo Rapaport, only laid eyes on the vehicle a few days before joining us on the trip.

Among its accessories, the Land Cruiser had a full-length Eezi-Awn “K9” roof rack supporting an Autohome Columbus roof tent. Adolfo was delighted with the effortless setup of the clamshell tent (undo latch, climb in, go to sleep); however, an ominous development hinted at future issues: One of the six brackets supporting the rack failed on the third day of the trip. The aluminum base of the bracket cracked completely through where three holes are drilled in a horizontal line for connection to the steel upper bracket—an obvious potential failure point. Soon another bracket failed, then another. Each time the brackets were shuffled to retain support at the corners, but finally we simply ran out of brackets.

On the second to last day of the trip the mounts gave way altogether, and we pulled the rack and tent off the Land Cruiser and strapped it to the massive construction rack of the Rawhyde F450 support truck that rendezvoused with us each night. Adolfo and his son Josh enjoyed a penthouse apartment from that point on; they just had to avoid an assortment of welding tanks and generators when clambering up and down.

Post-trip investigation by both the chagrined builder of the vehicle and the importer of the rack revealed that the brackets had been completely redesigned sometime after the last container left South Africa, indicating that Eezi-Awn had become aware of the essentially guaranteed failure rate of the original. New brackets (four for each side rather than three) are on the way to Adolfo as I write.

One other issue surfaced on the Land Cruiser: The dual battery mounts in the front of the engine compartment had been engineered so only the rear of each battery was securely clamped, and they quickly worked loose. Folded cardboard provided a temporary but less-than-stylish fix.

The two Jeep Wranglers performed very well, as I expected, although a plastic fitting for the transfer case linkage on one of them failed, and Phil had to secure it temporarily with a zip tie. After a long, slow climb, the automatic transmission oil temperature warning light came on in the other, but it never happened again. And Chrysler still has not solved the problem of mud thrown up from the front tires, which packed the front door handles of both Wranglers with goop. We had this issue with the long-term Wrangler Rubicon we had four years ago. C’mon Jeep—a simple set of abbreviated mud flaps in front would at least keep the arc of the flung mud below the handles.

One of the FJ Cruisers sported a custom combination tire carrier and mount for two four-gallon Roto-Pax fuel containers. The assembly was welded to the stock tire carrier base on the rear door, and early on the four welds began to fail one by one. Fortunately Phil was able to re-weld the mount sufficiently to keep it intact for the remainder of the trip. The location of the Roto-Pax significantly increased the leverage on the mount; I think the fabricator should rethink the design.

Sterling Noren’s clever Chevrolet conversion kept up effortlessly with all the more technologically advanced and prepared four-wheel-drive vehicles, and survived numerous blasts of speed as he raced ahead of the main group to film. But late in the trip, and late each day, the vehicle began dying at random and refusing to move more than a few feet unless it was allowed to cool for an hour or so. No codes showed on the OBD reader, and standard diagnostic investigation was futile, so Sterling simply let the van have a nap when needed.

Both Raptors performed flawlessly, as did both Tacomas. Ross Blair's Tacoma benefitted from conscientious daily checks.

And that 1990 Bronco? It survived the trip in style as well.

On a related note, both Four Wheel Campers performed as they always do, providing a home away from home with a two-minute setup time, and scarcely affecting the backcountry abilities of the vehicles to which they're attached. With that said, the turnbuckle attachment system continues to require frequent checking; I'm determined to come up with a way to solidly anchor them. And, for the second time on ours, a silly strip of rubber trim around the front overhang came loose on a windy stretch of interstate, making a noise all out of proportion to its importance. Quibbles on a superb product, but needing attention.

Other tidbits: Phil, who was towing an enclosed cargo trailer along a very muddy track in our wake on one of the easy sections, looked in his mirrors to note both fenders so loaded with sludge that they were ripping free of the trailer. He unbolted both and tossed them in the bed.

At one point I took over driving a two-wheel-drive support van shod with street tires along a level but treacherously slick muddy section, amusing the following drivers with the yaw angles I achieved while trying to keep the thing on the road. Luck was with me and I avoided ditching it. Total number of vehicle recoveries was remarkably low at three.

Oh, and, regarding Phil and the marshmallows? He proved remarkably apt at toasting them for s'mores with his oxy-acetylene torch.

Update

on 2014-06-12 00:52 by Jonathan Hanson

An update: Michael Collier, the owner of one of the Sportsmobiles that suffered a water leak, reports that the source in his was a connection between the water pump and the lower water tank. These connections have large knurled fittings that are designed to be hand-tightened. Once snugged, Michael says, the system has remained secure. The long-term solution seems to be regular checks while attending to basic daily maintenance.

Accessible wonders

Many years ago, while on an assignment for Outside magazine, I was graced with the incomparable experience of viewing Victoria Falls for the first time by walking up to the edge of the drop on Livingstone Island, right in the middle of the mile-wide cascade, after arriving by canoe, just as David Livingstone had almost exactly 150 years before. The breath literally left me; I gasped and very nearly wept at the sight. Only the terror of totally losing my cool in front of my guide kept me halfway composed.

Much more recently—last week in fact—I was graced with another first: driving out of the tunnel on California State Highway 41, the Wawona Road, and seeing Yosemite Valley spread out before me below sweeping clouds and mist. El Capitan rose on the left in an impossible vertical wall; Bridalveil Fall plunged in a gossamer thread on the right.

To paraphrase: The breath literally left me; I gasped and very nearly wept at the sight. Only the terror of totally losing my cool in front of my wife kept me halfway composed.

It was a good lesson in something many of us tend to forget: You don’t necessarily need to travel to Zambia (or fill in the blank) to have a once-in-a-lifetime experience. We were two easy day’s drive from home, and the sum total of our off-pavement excursions to that point had been about 500 yards of dirt road to reach a Forest Service dispersed campsite. Yet that view of Yosemite Valley will forever live in my memory directly alongside that first vertiginous peek over Victoria Falls.

The two natural wonders share more than you might think. Both were “discovered”—i.e. sighted for the first time by a person of European stock—in the mid-1800s, after of course being well-known to the locals for ages. In both cases, the “discoverers” were on profit-driven missions: Joseph Walker was looking for furs when he stumbled on Yosemite Valley, and Livingstone hoped to find a water route into the heart of the African continent. Both sites are now overrun with tourists pursuing, at times, tangent activities that seem utterly superfluous to me: I’ve said frequently that if you view Victoria Falls for the first time and think, Okay, cool—now I need to go bungee jumping off the bridge, then there’s something seriously wrong with your sense of wonder.

Yet the grandeur of both places effortlessly transcends the swarms of humans buzzing around them. Even at Yosemite, we found a trail along the Merced River, under El Capitan, on which in four miles we met two other people. And at Victoria Falls I spent a night camped on Livingstone Island (alone except for an askari), and got up at midnight to see the “moonbow”—a rainbow caused by moonlight shining through the mist of the falling water. Later I was awakened by the sound of foraging elephants, which wade to the island at night to feed.

So maybe I shouldn’t complain that everyone else was off bungee jumping.

The author, alone at dusk on Livingstone Island. The bungee jumpers are off toasting their adventure somewhere.

The author, alone at dusk on Livingstone Island. The bungee jumpers are off toasting their adventure somewhere.

Three days on El Camino del Diablo

Few places on earth have experienced such a completely circular human history as the desert traversed by southern Arizona’s El Camino del Diablo. In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries its harsh plains and jagged mountains comprised a gauntlet for missionaries, explorers, and seekers of gold traveling northwest from Caborca to the first sure water at the Colorado River. In the late 20th and early 21st centuries it became another gauntlet, this time for illegal immigrants from Mexico and Central America trekking north seeking the gold of employment in the U.S. The tally of deaths from either period is impossible to pin down, but likely very similar. Some say each is in the hundreds.

Yet like many landscapes that have witnessed human tragedy, the magnificence of this corner of the Sonoran Desert transcends the strivings and failings of the bipedal creatures that scratch its surface. Here is a region where temperatures in summer regularly exceed 115 degrees Fahrenheit, yet where biological diversity is higher than in the pine-clad Rocky Mountains. Here lives a species of fish—found in just one spring-fed pond—that can survive water temperatures of 95 degrees and salinity higher than the ocean. The bighorn sheep that look down from the cliffs can lose 30 percent of their body weight to dehydration and survive with no ill effects. Within multi-holed mounds on the desert floor is a small rodent, the kangaroo rat, that never drinks or even needs to eat moist vegetation. It manufactures its own water from the carbohydrates in the dry seeds that comprise its entire diet. When winter rains are plentiful—meaning a few inches—the desert floor explodes in spring with a show of wildflowers to rival any English meadow. And always, always, the open space gives new room to lungs constricted by city living, and sharper vision to eyes clouded by concrete horizons.

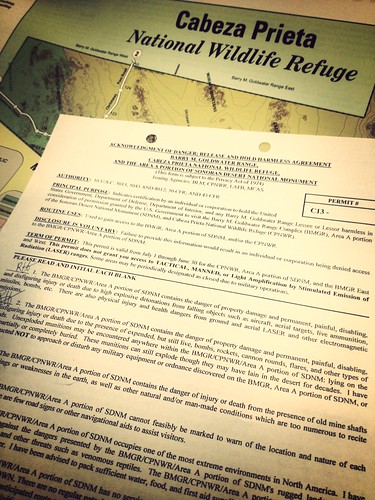

I first traversed "The Road of the Devil" in the sultry August of 1979, alone in my FJ40. In a week I saw not another soul—as far as I know, I had a million acres all to myself. That has changed, and although the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge and the Barry Goldwater Air force Range, through which the road passes, remain remote and rugged, the U.S. Border Patrol now maintains a persistent presence, with two F.O.B.s (forward operating bases) plonked down surreally in the desert, and constant patrols. Before you can get a permit as a new visitor, you’re required to watch a 15-minute video and sign off on a hold-harmless form detailing at least 27 ways a stupid person could get hurt or be blown to smithereens in the area.

It’s worth it. The landscape along the main road from Ajo south and west through a corner of the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument, across the Growler and Mohawk Valleys and the Tule Desert, is breathtaking, and changes with each pass through the mountain ranges—some dark, some light, some weirdly striped—that angle northwest/southeast through the refuge. The soft peach Pinta Sands dunes stand out in contrast to the surrounding lava fields, and improbable stretches of tightly overhanging mesquite trees mark the courses of washes that turn the road into impassible muck during summer thunderstorms.

The entire center section of the Camino is closed to public use from March 15 to July 15 to minimize disturbance to the secretive and endangered Sonoran pronghorn during fawning season—although the impact of the Border Patrol and migrants must be far greater than that of the few tourists who still brave the route. But if you wish, you can still drive in to the spectacular Tinajas Altas tanks from the west.

We beat the closure and spent a too-short weekend driving from Ajo to Tule Well, then north through Christmas Pass to Interstate 8. While some parts of the road are rough, and there are miles of corrugations north of Christmas Pass, we could have done the trip easily in a two-wheel-drive truck—or a sedan—in these conditions. West of Tule there are sections of bulldust that would challenge a low-clearance vehicle, however.

A four-wheel-drive Tacoma is almost overkill on El Camino. We're doing our best to abuse the stock street tires that came with the truck before mounting some all-terrain rubber.

A four-wheel-drive Tacoma is almost overkill on El Camino. We're doing our best to abuse the stock street tires that came with the truck before mounting some all-terrain rubber. Our first camp was at Papago Well, where a relief station and emergency beacon set up for migrants is marked with a blue flag.

Our first camp was at Papago Well, where a relief station and emergency beacon set up for migrants is marked with a blue flag.  Marisa stands amid the Pinacate lava flow, the northernmost extension of the Pinacate volcanic region. Near here is also the northernmost extension of the Altar dune field, called the Pinta Sands.

Marisa stands amid the Pinacate lava flow, the northernmost extension of the Pinacate volcanic region. Near here is also the northernmost extension of the Altar dune field, called the Pinta Sands. Looking down on Tule Well and the campsite (one of four on the refuge). The little cabin was built in 1989, replacing an earlier structure. A log book is inside for visitors to sign.

Looking down on Tule Well and the campsite (one of four on the refuge). The little cabin was built in 1989, replacing an earlier structure. A log book is inside for visitors to sign. Tule cabin is open and available for anyone to use if needed. There's even a small fireplace in the corner.

Tule cabin is open and available for anyone to use if needed. There's even a small fireplace in the corner.

Boy Scout troops erected this monument on the hill overlooking tule Well.

Boy Scout troops erected this monument on the hill overlooking tule Well.

Campfires are permitted, but you must bring your own wood. We also used a sturdy Snow Peak Pack & Carry fireplace.

Campfires are permitted, but you must bring your own wood. We also used a sturdy Snow Peak Pack & Carry fireplace. Dawn from Tule Camp. Mockingbirds and Phainopeplas were getting ready to breed, and singing.

Dawn from Tule Camp. Mockingbirds and Phainopeplas were getting ready to breed, and singing. Heading north through Christmas Pass, affording a fine view of our ultra-low-profile Global Solar photovoltaic panels, which provide the Four Wheel Camper with a surfeit of power.

Heading north through Christmas Pass, affording a fine view of our ultra-low-profile Global Solar photovoltaic panels, which provide the Four Wheel Camper with a surfeit of power. Under a cloudy sky we headed north toward I-8, past this enormous ironwood tree.

Under a cloudy sky we headed north toward I-8, past this enormous ironwood tree. Lots of unexploded ordnance on the Barry M. Goldwater range. This fin could be a piece, or there could be an entire missile under there. Do we pull on it?

Lots of unexploded ordnance on the Barry M. Goldwater range. This fin could be a piece, or there could be an entire missile under there. Do we pull on it? Federal law states that it illegal to visit the Cabeza Prieta without stopping at Dateland afterwards for a zillion-calorie date shake. Well, if it's not illegal, it should be. Support local business!

Federal law states that it illegal to visit the Cabeza Prieta without stopping at Dateland afterwards for a zillion-calorie date shake. Well, if it's not illegal, it should be. Support local business!

If you go: The refuge headquarters and visitors' center is in Ajo, on the road north out of (or into) town (Monday through Friday 8:00 to 4:00). You're required to obtain a free permit to enter the refuge, and will also need to register at a kiosk on the refuge border. The roads through the refuge are easily traversed, but a sturdy vehicle is recommended. You could drive the length in a day if you really wanted to, but it would be a wasted journey not to slow down and experience the scenery and wildlife.

Take plenty of water—there are no reliable sources on the refuge, and what's there is needed for wildlife. Take enough to ensure you could walk out to the nearest highway if necessary; don't count on a Border Patrol agent coming along to rescue you.

A fine book on the Camino del Diablo is Sunshot, by Bill Broyles.

View our entire collection of trip photos on Flickr, here, and our video highlights, below.

More good stuff from Lifeproof

I’m not as technologically averse as all my friends and family like to joke. In fact, I pioneered the switch to Mac computers in our household in 2003, and managed to learn the new operating system pretty much on my own. Digital cameras? I was all over them once the images reached publishable resolution.

However, I will admit to a fierce, abiding loathing for the telephone, or, to be specific, talking on the telephone. For me it’s always been a tool for dispensing or receiving important information as quickly as possible, not for leisurely chats. There are few phone conversations I can’t get through using artful combinations of “Yes,” and “No,” occasionally spiced with “Sure,” or “Probably not,” including calls home to my wife after two weeks incommunicado in Zambia. Any interchange that goes over 30 seconds and my fingers start tapping, my pupils dilate, and a high-pitched keening sound becomes noticeable to the person on the other end. The torture scene in Zero Dark Thirty? Calls from my mother were worse.

And that’s why—until recently—a $19 flip-phone was all the phone I needed. I’d point over the counter at the Verizon store and ask, “Can that one in the back make calls?” If the answer was, “Well, sure, but . . .”—sold.

Then telephones started doing more than annoying me, because they started doing more than ringing. First they added GPS—astonishing enough—but then came apps and Google Maps, and suddenly on road trips Roseann could tap her iPhone and find the best coffee or café in any town on our route in seconds. No more fishing down side streets, gambling on local diners, or settling for anodyne chains. The facility made road trips far more enjoyable, and probably saved enough time to add a hundred miles to the distance we could cover in a day.

There was more, such as the level and tilt app that allowed us to precisely measure the angles of slip faces on dunes in Egypt’s sand seas. And the utterly magic Star Walk, which recently informed us that the bright satellite passing over our camp in the desert at dusk was in fact the International Space Station. And the National Geographic North American Bird Guide, which includes a complete audio section on calls and songs.

So . . . sigh . . . after losing my most recent throwaway phone somewhere in Africa, I became the owner of an iPhone 5—and, not ten minutes after regaining normal heart rhythm from sticker shock, learned about accessories. I remember when the only accessory for a phone was the rubber banana-shaped thing you stuck to the handset so you could hold it with your shoulder. Not anymore.

First addition was a Lifeproof case. And a fine addition it was, considering that for the last decade I’ve been used to treating my $19 phone like . . . a $19 phone. No need to walk clear across the room to put it on my desk—a simple toss gets it there quicker. Not a good idea with a zillion-dollar miniature computer/phone/camera/GPS thing, but old habits die hard. So the shock-resistant, waterproof Lifeproof case gives me peace of mind. Furthermore, it vastly improves my grip on the phone, which when nude had an unsettling orange-seed squirtiness about it, like it could fly out of my grasp on its own. It necessitates a slightly firmer tap to use the touch-screen, but not much, and since I do not text, facile typing is unnecessary. I note that Roseann, who frequently answers business emails on her iPhone while I’m driving, doesn’t seem to have a problem.

Most recently we received one of Lifeproof’s suction-cup vehicle mounts. It can attach to the windshield, but the kit includes a disk with adhesive backing you can stick elsewhere on the dash if you don’t want the unit in your line of sight of the road. We attached the disk to the passenger side of the center console, clipped in the phone, and left for a weekend trip along southern Arizona’s Camino del Diablo, which sports miles and miles of punishing washboard (or corrugations as the rest of the world knows them), especially along the Christmas Pass exit road to I-8. The iPhone on its mount remained astoundingly vibration-free throughout the trip, and Roseann had no trouble tapping in navigation commands without the need to support the unit from behind. It’s a solid system, and well worth its $40. Of course it’s sized to take the iPhone only if it’s inside a Lifeproof case, and we’d need another model for Roseann’s slightly smaller iPhone 4S (it fits but not as securely). But I suspect if they made it one-size-fits-all the rigidity would suffer, so I won’t complain.

I recall how thrilled I was with our old Garmin 276 GPS and its bulky, jiggly windshield suction mount. Just five years later we have a device that does ten times more at a fifth the weight, and a mount that renders it as steady and accessible as if it were another dashboard gauge.

Isn’t technology wonderful?

The trusty Motorola 9500

Shortly after we published the story of our BGAN review in Mexico (here), which became a real-life test of the technology, I got an email from our friend John Knights, a senior Land Rover Experience instructor in the UK who’s also been on and led many major expeditions in Africa. John bought one of the very first Motorola 9500 satellite telephones in 2001, and has been using it since.

Shortly after we published the story of our BGAN review in Mexico (here), which became a real-life test of the technology, I got an email from our friend John Knights, a senior Land Rover Experience instructor in the UK who’s also been on and led many major expeditions in Africa. John bought one of the very first Motorola 9500 satellite telephones in 2001, and has been using it since.

The 9500 was a bellweather in the development of satellite telephones. When I made my first sat phone call in 1999, from a camp in Zambia, the device I used required a bulky tri-fold antenna which had to be precisely aligned, and which came with dire warnings not to stand within three meters of the front of it. Just two years later, when the financially troubled Iridium network finally got up and running for the final time, you could make the same call with a one-piece handheld 9500 and stand anywhere you wanted (as long as it was outside).

Since then, John has used his 9500 on more than one occasion to manage emergencies in the bush—some of them mere inconveniences, some of them more serious. Here are a few of his recollections.

Zimbabwe 2001 (chasing a total solar eclipse in the north of the country): The Defender 130 we had hired blew out two tire sidewalls. Although it was equipped with two spares, once both were used we would have been stranded had we suffered another blowout—highly likely on remote African dirt roads. A quick call to the hire company office had two spare tyres and inner tubes on a light aircraft to a nearby safari lodge, who dropped them off in a powerboat to where we were camped on the shores of Lake Kariba.

Death Valley 2002 (touring the scenic Wild West in a rented SUV): We had journeyed off the beaten track to see the famous moving rocks. Returning down the rough dirt track, we were passed at speed by another SUV. They shot off into the distance, and I commented, “He must have much better suspension to travel at that speed on this road.” A few corners later we found the SUV, wrecked—he had lost control and hit an embankment, launching the car airborne, going end over end twice before landing back onto its wheels. Thankfully the occupants where unharmed, but had no supplies or recovery gear with them and were surprised their mobiles did not work. I produced my trusty Motorola, rang the ranger station number off the park map, gave them our exact position from my GPS, and waited until the rangers arrived. In the meantime we found out the family concerned were also in a rented SUV and were due to fly home that evening. I’d love to know what he told the hire company!

Australia’s Blue Mountains 2003: Touring in a hired car we came across a 4x4 on its side. The driver had gotten into a skid on the loose gravel road, and aimed for the embankment rather than the drop off. Again everyone safe but no mobile coverage, but a swift call from the Iridium had a rescue on the way.

Namibia 2003: We set a new record on this trip for number of days without a puncture (seven I think), but that meant we were in the middle of nowhere when the first one happened. The puncture itself was not a problem, but when the locking wheel nut key split while reinstalling the wheel, it did create a problem when we had a second puncture and could not remove the locking nut. Again an Iridium phone call to the hire office had a man with a hammer and chisel on the way, although we did have to spend an unexpected extra night out on route. Our journey was not actually saved by the man with the chisel, but buy the sister vehicle to ours from the hire fleet. The guests driving it rolled it over a couple of miles from where we were. Armed with their wheel nut key we were able to remove our flat tyre, and we then took normal wheel nuts and spare tyres from the wrecked 110 to allow us to continue.*

Whilst I would love to have an all-singing-all-dancing satellite communication set up that gave me calls, high-speed internet, and a wifi hotspot, at the end of the day the ability to raise any help is a blessing and I’m sure my trusty 9500 will see a few more adventures yet.

Ocens (here) carries the full line of Motorola satellite telephones, including the current 9555.

* An easy trick (no doubt discovered by wheel thieves) is to find a 12-point 1/2-inch drive socket that's just too small to fit over the locking lug nut, hammer it over the nut, then use a breaker bar to remove it. I've used the technique a half-dozen times and have yet to fail. JH

Easy trip assistance app

by Roseann Hanson

by Roseann Hanson

How many times have you been reading a magazine or book, and come across some place you want to jot down to remember to visit, such as a landmark, a restaurant, a museum, or a trail?

In the past I either scribbled these onto a nearby post-it note or in a file on my computer. Inevitably these got lost in the shuffle of life, or are too difficult to locate when I knew I was going to be in a certain place, or I just plain forgot to bring my file with me.

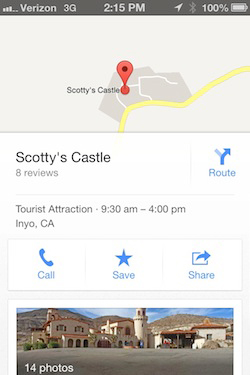

Recently friends mentioned how interesting Scotty's Castle was on their overland trip through Death Valley. I started to jot it down in a notebook in the truck, but then thought, I wonder if there is an app for that?

Ever the fan (and growing) of organizing my life by iPhone, I searched the AppStore for "record places" or "remember places." One of the first to come up was the very promising My Places by VoyagerApps.com. Using your GoogleMaps account, it promises to let you see and organize your saved "places" in real time. I downloaded the free version to test it out, but unfortunately it was so annoying, I deleted it. The free version won't let you do anything without constant interruptions from pop-up notifications asking if you want to download and try other apps (presumably by VoyagerApps.com)—a different ad popped up every 30 seconds, literally, and you have to stop and click "No, thanks" every time. Then it would not let me save anything or see my Google places unless I bought the app, so I could hardly see if it worked or not. I don't mind buying apps, but this was a real stinker.

Then I tried a cool-sounding app called PintheWorld, which allows you to pin and save places of interest, give them categories (different colored pins, too), and see them when passing through a location. Sounded perfect! But unfortunately the developer uses the new iOS 6 in-house (and yes, totally lame) Apple Maps app and it is so inaccurate and picky, I could not find businesses I knew were there. The trick turned out to be that you have to type the exact, and I do mean exact, address down to the country and zip code. And then you have to manually name it and add details. Too much work. I just knew, with the power of the Internet and Apple, there had to be a solution.

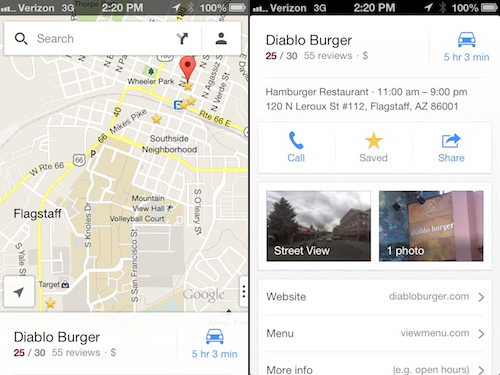

Turns out it was right there all along: Google just released their brilliant Google Maps app for iPhone—pair it with your Google Maps account, and you're good to go.

(For those of you who haven't followed the little cyber drama between Google and Apple, Google was the original driver behind the superb Maps app on the iPhone but last year Apple and Google's relationship melted down, and Apple replaced Google as the data source with TomTom. My own side-by-side comparision between Google Maps and the Apple iOS 6 Maps bore out all the crazy criticism of the incredibly bad app. The famous tech geek David Pogue even called it "the most embarrassing, least usable piece of software Apple has ever unleashed." I could call up Google Maps, looking for the new Wanderlust Brewery in Flagstaff and up it pops . . . on Apple's Maps it fails to find anything, or sends me to Connecticut.)

But back to how to use the Google Maps and your Google account to save cool places to visit (after downloading Google Maps app you need to pair it with your online Maps.Google.com account).

I wanted to save Scotty's Castle as a place of interest, so I just hit the search bar, typed in Scotty's Castle, and up it pops (see screen shot, right). Swipe up on the name Scotty's Castle in the bar at the bottom, and it gives you a menu of buttons—Call, Save, Share. Hit Save, and it puts it into your Google Places.

I wanted to save Scotty's Castle as a place of interest, so I just hit the search bar, typed in Scotty's Castle, and up it pops (see screen shot, right). Swipe up on the name Scotty's Castle in the bar at the bottom, and it gives you a menu of buttons—Call, Save, Share. Hit Save, and it puts it into your Google Places.

On this screen you can also browse things like photos, hours, reviews, distance from current location, and other useful information.

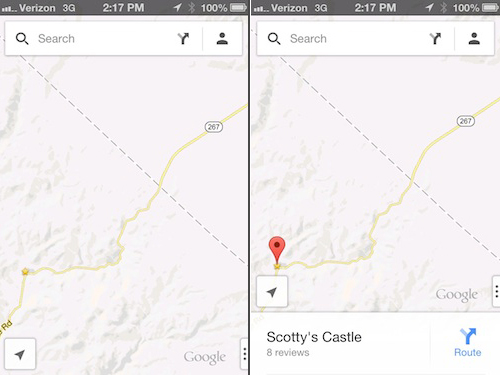

Then, next time I'm in Death Valley area, and I want to see if it's nearby, I fire up Google Maps app and any saved Places show up as yellow stars (see below).

I am trying to find out if the star colors can be changed, because the yellow is hard to see against the yellow roads. And they only show up at a certain zoom magnification.

The next screen-shot set below shows all the restaurants and cafes saved for Flagstaff, near Overland Expo. Click on a star and a pin pops up; click on the pin and you get the easy-to-read information popup at the bottom (swipe it up to see the details).

Ideally Google will eventually let us categorize and organize our Places, and edit them from either the app or through the Maps.Google.com. It would be nice to filter for things like restaurant, art gallery, museum, trail, or other category, to help minimize clutter if you have marked a lot of places in one area.

But otherwise it looks like it's going to be a very useful tool for travel anywhere.

Google Maps app is great for storing places you want to visit, like these restaurants and cafes in Flagstaff, near Overland Expo.

Google Maps app is great for storing places you want to visit, like these restaurants and cafes in Flagstaff, near Overland Expo.

Special report: Adventure Overland UK Show

Those of us in the U.S. overlanding world have always assumed that our English counterparts were well ahead of us. They invented the Land Rover, after all (not to mention those awesome MOD water cans with the little brass chains to secure the cap and breather). And they can take the Chunnel to Calais, turn right, and be in Morocco in about 24 hours, or continue straight on to the Silk Road. Plus, South Africa—which was of course a British colony for ages—is the source for much of the premier overlanding equipment on the market, from such stellar names as Howling Moon, Front Runner, Eezi-Awn, National Luna, and a host of others.

It seems, though, that while the English did get a head start on us Yanks in terms of access to proper equipment, their overland community has until now lacked any sort of real cohesion. Four-wheel-drive shows have tended to focus on hard-core abandoned-quarry rigs, the corollary to rock-crawlers here. The venerable Horizons Unlimited meets were dominated by motorcycles.

Meanwhile, in the U.S., the Overland Expo—which will celebrate its fifth anniversary in 2013—has brought together an extended overlanding family that now views each year as much a reunion and a chance to catch up on each other’s news as an educational and product show. (And our number one source of foreign attendees? Great Britain, of course.)

That’s at least partly why Tom McGuigan, who owns Off Road UK and has promoted several other vehicle-related shows in Great Britain, decided to put together the Adventure Overland Show, an overland-specific event in Daventry, a few hours northwest of London. He generously invited Roseann and me to attend, and put us up in a tent at least as big as our cottage at home—it could have effortlessly doubled as a garage for one of the dozens of nearby Defenders. [And Tom's partner Shiela made sure we had extra comforters and pillows against the cold—much appreciated.]

[SEE OUR COMPLETE PHOTO SET ON OUR FLICKR ACCOUNT, CLICK HERE.]

We felt right at home situated between Overland Expo regulars Austin Vince and Lois Pryce on one side and Toby Savage on the other. Just behind us was Jens of Wohnkabinencentr.de, who is importing Four Wheel Campers into Europe, modified slightly in interior decor and names (the Wildcat is the Fleet in North America).

Not far away was another friend and Expo alumnus, Chris Scott, who’d borrowed a car to bring boxes of his latest Overlander’s Handbook, samples of which were laid out on—could that really be?—yes, an ironing board wrapped in a bit of colorful cloth. Chris, we know you’re skint, but . . .

If what we saw in this first event is any indication, the Adventure Overland Show has a bright future. There were dozens of vehicles set up for long-distance travel, vendors of equipment (including those MOD water cans—tragically no room in our Kenya-bound luggage), tour companies (including Transylvania Tours, whose logo is—what else—a smiling cartoon Bella Lugosi with fangs), and, set off in a corner, a booth for the Parrot Rescue Association (no idea, but a worthy endeavor). One delightfully British genre is the bushcraft community; there were several vendors of volcano kettles and proper scandi-grind knives, and a spot where kids of any age could learn how to use flint (well, okay, magnesium) and steel to start a fire.

Much on offer at the Adventure Overland Show was identical to what we see at the Overland Expo, happy confirmation that dedicated overlanding equipment has made a nearly complete transition to U.S. suppliers—in fact I’d venture to say we might just be edging ahead in terms of variety. But there was some interesting exotic kit. Did I mention the MOD water cans? Right.

Long-distance travelers wanting a compact home on a Land Rover chassis could look at the L’Azalai campers. Built of a 20-millimeter-thick composite, the L’azalai fits either the 110 or 130 Defenders, and incorporates a complete galley with sink, stove, and fridge, a dinette, a hanging closet, and a large bed. Since it’s chassis-mounted, there’s even a (tight) pass-through into the cab. The L’Azalai just manages to avoid the Queen Alien look of so many add-on campers; especially on the 130 chassis.

David Bowyer of Goodwinch claims to have taken the Chinese-manufactured winch to a higher level, with better waterproofing, stronger motors, and cone brakes that eliminate the overheated line that can be caused by a drum brake. He’s one of the few—no, strike that, he’s the only winch importer I’ve seen happy to display the internals of his Asian-made winches.

If I had to pick a favorite product at the Adventure Overland Show, it would be the Cap Lander camper made for Defenders and Japanese pickups. Constructed of a honeycomb composite that’s not only light and rigid, but also insulative and partially translucent to brighten the interior, the slide-in unit comprises an astonishingly space-efficient portable home—bed, sink, shower, stove, porta-potti, etc.—in a 600-pound package. Look for a more in-depth review of the Cap Lander soon in Overland Tech and Travel.

[SEE OUR COMPLETE PHOTO SET ON OUR FLICKR ACCOUNT, CLICK HERE.]

Overall, Tom McGuigan did a wonderful job bringing together the British overland community in this first event. We wish him all the best in the future, and we look foward to being at the Adventure Overland Show 2013 in an even greater capacity.

[We also just heard from Iain Harper that HUBBUK will be hosting an expanded show in late May 2013 in Leicestershire, incorporating more 4x4 overlanding as well—great to hear!]

Land Cruisers of Baharia, Egypt

Land Cruisers of Baharia, Egypt—a set on Flickr

Land Cruisers of Baharia, Egypt—a set on Flickr

The oasis of Baharia, about five hours south of Cairo, is the gateway to the Western Deserts and a major hub for expedition services and vehicles.

On our way there during the Sykes-MacDougal Centennial Expedition in February 2012, we heard there was a booming trade in all things Land Cruisers, but we were not prepared for the sheer numbers of every year and model.

There were plenty of new, expensive examples, but there were many custom amalgamations that sometimes boggled the mind. Apparently, to avoid the high import duties on any vehicle (new or used), canny Egyptian mechanics in Baharia started bringing in cut-up halves and quarters of Land Cruisers from neighboring countries, and then welding them back together after arrival—voila, a duty-free Land Cruiser.

These photos were taken in just one day plus part of a morning, not even a full 8 hours in the town during daylight. There were hundreds—literally half the vehicles in town were Land Cruisers. Almost all the images are snapshots, taken out the window as we drove or shot quickly while walking. I included a couple of interesting non-Toyota shots.

Hint: When using “Search,” if nothing comes up, reload the page, this usually works. Also, our “Comment” button is on strike thanks to Squarespace, which is proving to be difficult to use! Please email me with comments!

Overland Tech & Travel brings you in-depth overland equipment tests, reviews, news, travel tips, & stories from the best overlanding experts on the planet. Follow or subscribe (below) to keep up to date.

Have a question for Jonathan? Send him an email [click here].

SUBSCRIBE

CLICK HERE to subscribe to Jonathan’s email list; we send once or twice a month, usually Sunday morning for your weekend reading pleasure.

Overland Tech and Travel is curated by Jonathan Hanson, co-founder and former co-owner of the Overland Expo. Jonathan segued from a misspent youth almost directly into a misspent adulthood, cleverly sidestepping any chance of a normal career track or a secure retirement by becoming a freelance writer, working for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and nearly two dozen other publications. He co-founded Overland Journal in 2007 and was its executive editor until 2011, when he left and sold his shares in the company. His travels encompass explorations on land and sea on six continents, by foot, bicycle, sea kayak, motorcycle, and four-wheel-drive vehicle. He has published a dozen books, several with his wife, Roseann Hanson, gaining several obscure non-cash awards along the way, and is the co-author of the fourth edition of Tom Sheppard's overlanding bible, the Vehicle-dependent Expedition Guide.