Blood & Leather: Saving the art of the Maasai war shield

Story and images by Jonathan & Roseann Hanson

Dust roiled around us, a khaki African veil, as Jonathan pushed the Land Rover up past 50 kph—the fastest we'd been able to go since we'd left Nairobi on the way to Magadi and the Great Rift Valley, not far from the Tanzania border.

Like in most African countries—from Egypt to Zambia—the dirt roads of Kenya are where you can travel fastest. If there are paved roads, they are so pocked with potholes and packed with pedestrians, bicycles, and livestock that locals have a saying: "You know how you tell a drunk driver in Africa? They are the only ones driving straight."

It was early October 2011, the dry season between the short and long rains in East Africa, and we were on our way to help host a law enforcement training workshop for the South Rift Game Scouts through our small charity, ConserVentures, whose mission is to promote exploration of the planet and conservation of its natural and cultural resources. The South Rift Game Scouts are an anti-poaching squad protecting the abundant wildlife of the Maasai nature conservancies in the southern Rift Valley; they receive no funding or support from the Kenyan government. Since 2006 we have been working with the African Conservation Centre in Nairobi to develop support for community-based projects, especially those of the Maasai whose territories overlap the most wildlife-rich landscapes in East Africa.

Click to enlarge map.

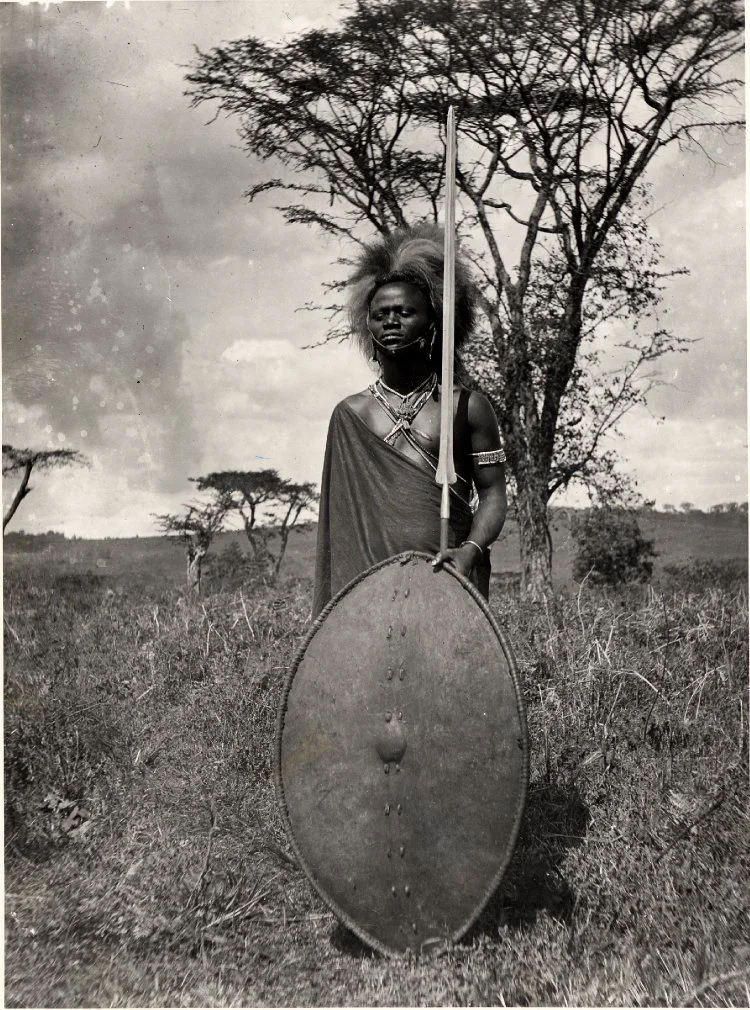

The Maasai are among the most famous of Africa’s people, known for their distinctive red robes called shukas, their pastoral traditions, and their history as fierce warriors. For 300 years they ruled a broad swath of the Rift Valley region in what is now Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania. As semi-nomadic pastoralists originating in the upper Nile, they moved their cattle in response to rainfall patterns, mimicking the migration routes of wild game and leaving little or no permanent impact on the land. When they needed more cattle, they raided other tribes.

In the early 1900s, British colonial officials exploited the nebulous and fractious nature of Maasai leadership to craft several treaties that drastically diminished existing Maasai territories and further curtailed the ability of tribal members to move their herds with the rains. The increasingly forced sedentariness of Maasai life became a challenge that has yet to be fully solved.